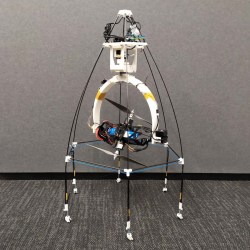

What can drive on the ground, hop in the air, and continuously move its coaxial rotor assembly without ever having to reset its position? The answer is [New Dexterity]’s Omnirotor All-Terrain Platform.

Although still very much a prototype, the video below the break shows that the dexterity claimed by Omnirotor isn’t just a lot of hype. Weaving through, around, and over obstacles is accomplished with relative ease by way of a coaxial rotor configuration that’s sure to turn some heads.

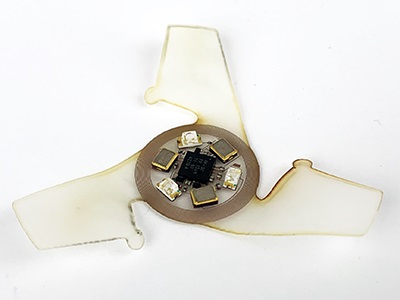

While not novel in every aspect, the Omnirotor’s strength comes from a combination of features that are fairly unique. The coaxial rotors are fully gimballed, and as such can be moved to and from any direction from any other direction. In other words, it can rotate in any axis infinitely without needing to return to a home position. Part of this magic comes from a very clever use of resources: The battery, speed controllers, and motors are all gimballed as one. This clever hack avoids the need for large, heavy slip rings that would otherwise be needed to transmit power.

Adding to the Omnirotor’s agility is a set of wheels that allow the craft to push itself along a surface, presumably to decrease power consumption. What if an obstacle is too difficult to drive around or past? The Omnirotor takes to the air and flies over it. The coaxial rotors are caged, protecting them from the typical rotor-snagging dangers you’d expect in close quarters.

[New Dexterity] has Open Sourced the entire project, with the Omirotor design, Firmware, and even the benchmarking platform available on Github so that others can share in the fun and iterate the design forward even further.

You might also enjoy this tetrahedron based omnirotor, or another omnirotor that knows how to play fetch. Really.

Continue reading “Gimballed Omnirotor Goes Over Great Obstacles”

![[Nick Rehm] explains the workings of a gps-less self guided drone](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/gpsless-drone-featured.jpg?w=600&h=450)