It can be hard enough to take a good photograph of a running kid or pet, and if we’re being honest, sometimes even stationary objects manage to elude our focus. Now imagine trying to take a picture of something moving really fast, like a bullet. Trying to capture the moment a fast moving projectile hits an object is simply not possible with a human behind the shutter button.

Enter the ballistic chronometer: a device that uses a set of sensor gates and a highly accurate timer to determine how fast an object is flying through it. Chronometers that operate up to a couple hundred meters per second are relatively common, but [td0g] had something a little faster in mind. He’s come up with an optical setup that he claims can capture objects moving as fast as Mach 2. With this chronometer tied into a high-speed flash rig, [td0g] is able to capture incredible shots such as the precise instant a bullet shatters a glass of water.

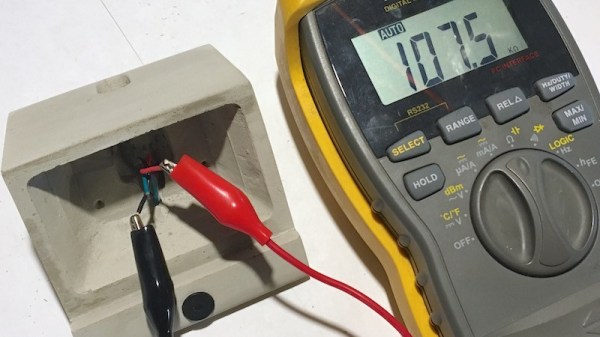

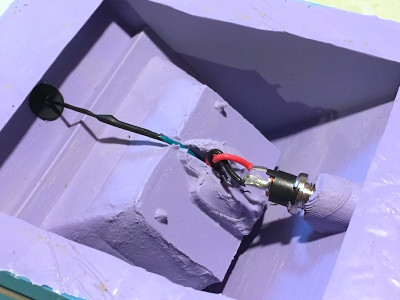

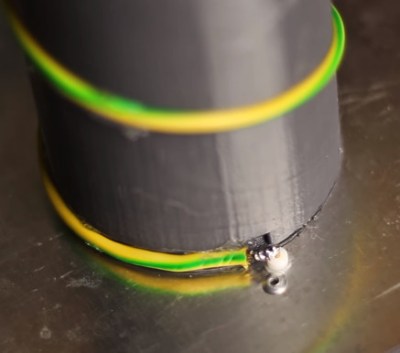

Because he couldn’t find any phototransistors with the sub-microsecond response time necessary to detect a small object moving at 1,000 m/s, [td0g] ended up using LEDs in a photoconductive configuration, where 27 VDC is applied backwards against the diode. Careful monitoring of voltage fluctuations across the diode allows for detection of changes in the received light level. To cut down on interference, [td0g] used IR LEDs as his light sources, reasoning there would be less ambient IR than if he used something in the visual range.

Because he couldn’t find any phototransistors with the sub-microsecond response time necessary to detect a small object moving at 1,000 m/s, [td0g] ended up using LEDs in a photoconductive configuration, where 27 VDC is applied backwards against the diode. Careful monitoring of voltage fluctuations across the diode allows for detection of changes in the received light level. To cut down on interference, [td0g] used IR LEDs as his light sources, reasoning there would be less ambient IR than if he used something in the visual range.

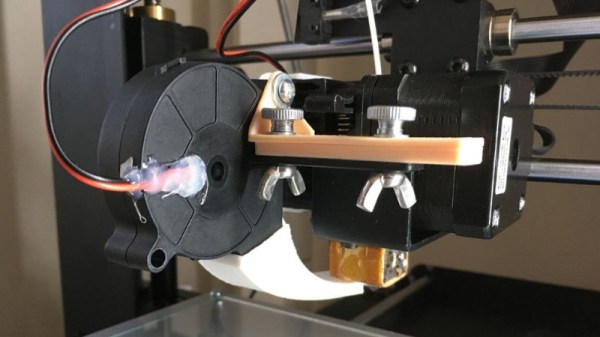

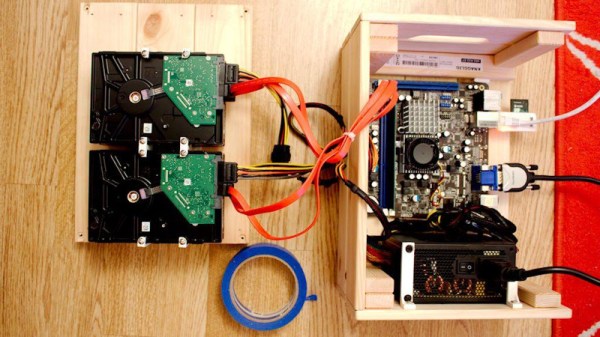

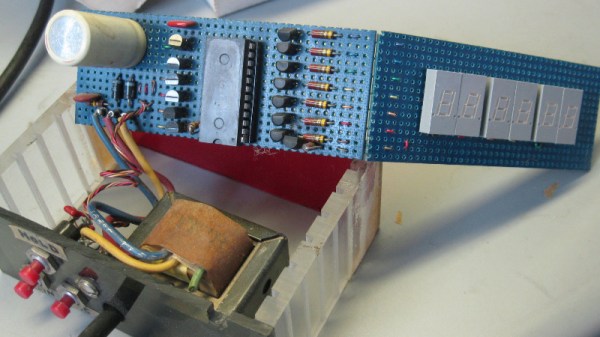

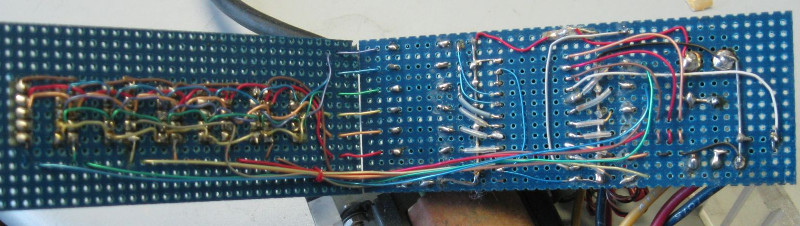

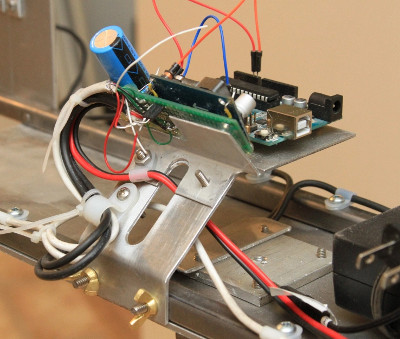

What really impresses with this build is the attention to detail and amount of polish [td0g] put into the design. From the slick angled bracket that holds the Arduino and LCD to the 3D printed covers over the optical gates, the final device looks like a professional piece of equipment with a price tag to rival that of a used car.

For the future, [td0g] plans on upgrading to faster comparators than he LM339’s he has installed currently, and springing for professionally done PCBs instead of protoboard. In its current state this is already a very impressive piece of kit, so we’d love to see what it looks like when it’s “finished”.

If you don’t need something quite this high end but still would like to see how fast something is going, we have covered chronometer builds to fit every budget.