A curious custom that survives from the pre-computer era is that of the business card. If you walk the halls at a trade event you’ll come a way with a stack of these, each bearing the contact details of someone you’ve encountered, and each in a world of social media and online contact destined to languish in some dusty corner of your desk. In the 21st century, when electronic contacts harvested by a mobile phone have the sticking power, how can a piece of card with its roots in a bygone era hope to compete?

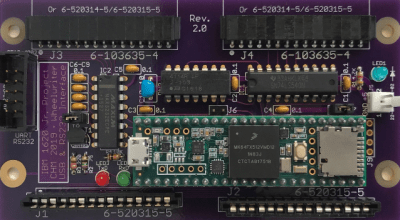

It’s a question [Anthony Kouttron] has addressed in the design of his thoroughly modern business card, and along the way he’s treated us to an interesting narrative on how to make the card both useful beyond mere contact details as well as delivering that electronic contact. The resulting card has an array of rulers and footprints as an electronic designer’s aid, as well as an NFC antenna and chip that lights an LED and delivers his website address when scanned. There are some small compromises such as PCB pads under the NFC antenna, but as he explains in the video below, they aren’t enough to stop it working. He’s put his work in a GitHub repository, should you wish to do something similar.

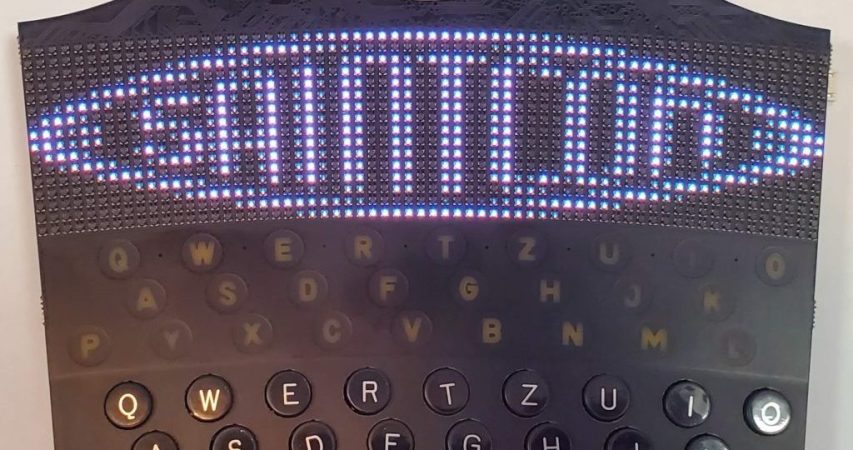

There’s a rich vein of business card projects on these pages, but so far surprisingly few are NFC equipped. That didn’t stop someone from making an NFC-enabled card with user interaction though.

Continue reading “There’s More To Designing A PCB Business Card Than Meets The Eye”