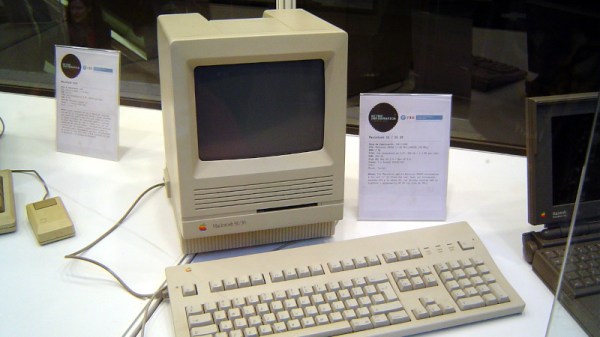

Back in the 1980s, printers were expensive things. Scanners were rare, particularly for the home market, because home computers could barely handle basic graphics anyway. Back in these halcyon days, an obscure company called Thunderware built a device to convert the former into the latter. It was known as the Thunderscan, and was a scanning head built for the Apple ImageWriter dot matrix printer. Weird enough already, but this device hides some weird secrets in its design.

The actual scanning method was simple enough; the device mounted a carriage to the printer head of the ImageWriter. In that carriage was an optical reflective sensor which was scanned across a page horizontally while it was fed through the printer. So far, so normal.

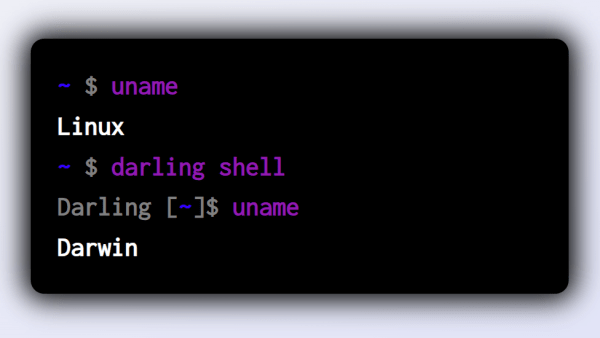

The hilarious part is how the scanner actually delivered data to the Macintosh computer it was hooked up to. It did precisely nothing with the serial data lines at all, these were left for the computer to command the printer. Instead, the output of the analog optical sensor was fed to a voltage-to-frequency converter, which was then hooked up to the handshake/clock-in pin on the serial port.

The hilarious part is how the scanner actually delivered data to the Macintosh computer it was hooked up to. It did precisely nothing with the serial data lines at all, these were left for the computer to command the printer. Instead, the output of the analog optical sensor was fed to a voltage-to-frequency converter, which was then hooked up to the handshake/clock-in pin on the serial port.

The scanner software simply looked at the rate at which new characters were becoming available on the serial port as the handshake pin was toggled at various frequencies by the output of the optical sensor. Faster toggling of the pin indicated a darker section of the image, slower corresponded to lighter.

Interestingly, [Andy Hertzfeld] also has his own stories to tell on the development, for which his software contribution seems to have netted him a great sum of royalties over the years. It’s funny to think how mainstream scanners once were; and yet we barely think about them today beyond a few niche uses. Times, they change.

Thanks to [J. Peterson] for the tip!