Most people remember Charles Lindbergh for his non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic which made him an international celebrity. If you are a student of history, you might also know he was at the center of a very controversial trial surrounding the kidnapping of his child or even that he had a dance named after him. But did you know he was also the co-inventor of a very important medical device? Turns out, medicine can thank Lindbergh for the creation of the perfusion pump.

Medical Hacks705 Articles

Permanent Artificial Hearts: Long-Sought Replacements May Not Be Far Away

The number of artificial prosthetic replacement parts available for the human body is really quite impressive. From prosthetic eyes to artificial hips and knees, there are very few parts of the human body that can’t be swapped out with something that works at least as well as the original, especially given that the OEM part was probably in pretty tough shape in the first place.

But the heart has always been a weak spot in humans, in part because of the fact that it never gets to rest, and in part because all things considered, we modern humans don’t take really good care of it. And when the heart breaks down past the point where medicine or surgery can help, we’re left with far fewer alternatives than someone with a bum knee would face. The fact is that the best we can currently hope for is a mechanical heart that lets a patient live long enough to find a donor heart. But even then, tragedy must necessarily attend, and someone young and healthy must die so that someone else may live.

A permanent implantable artificial heart has long been a goal of medicine, and if recent developments in materials science and electrical engineering have anything to say about it, such a device may soon become a reality. Heart replacements may someday be as simple as hip replacements, but getting to that point requires understanding the history of mechanical hearts, and why it’s not just as simple as building a pump.

Continue reading “Permanent Artificial Hearts: Long-Sought Replacements May Not Be Far Away”

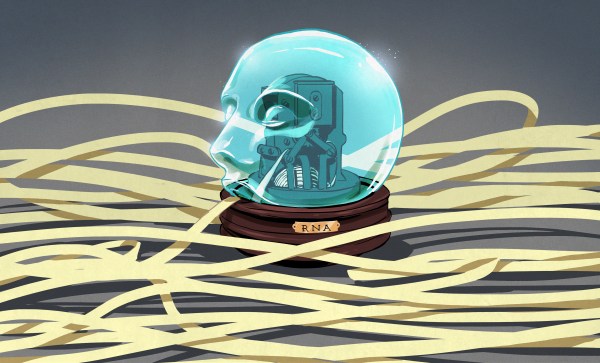

RNA Therapeutics And Fighting Diseases By Working With The Immune System

Before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic took hold, few people were aware of the existence of mRNA vaccines. Yet after months of vaccinations from Moderna and BioNTech and clear indications of robust protection to millions of people, it now seems hard to imagine a world without mRNA vaccine technology, especially as more traditional vaccines seem to falter against the new COVID-19 variants and the ravages of so-called ‘Long COVID’ become more apparent.

Yet, it wasn’t that long ago that Moderna and BioNTech were merely a bunch of start-ups, trying to develop profitable therapies for a variety of diseases, using the brand-new and largely unproven field of RNA therapeutics. Although the use of mRNA in particular for treatments has been investigated since 1989, even as recently as 2017 there were still many questions about safe and effective ways to deliver mRNA into cells, as per Khalid A. Hajj et al.

Clearly those issues have been resolved now in 2021, which makes one wonder about the other exciting possibilities that mRNA delivery offers, from vaccines for malaria, cancer, HIV, as well as curing autoimmune diseases. How did the field of mRNA vaccines develop so quickly, and what can we expect to see the coming years?

Continue reading “RNA Therapeutics And Fighting Diseases By Working With The Immune System”

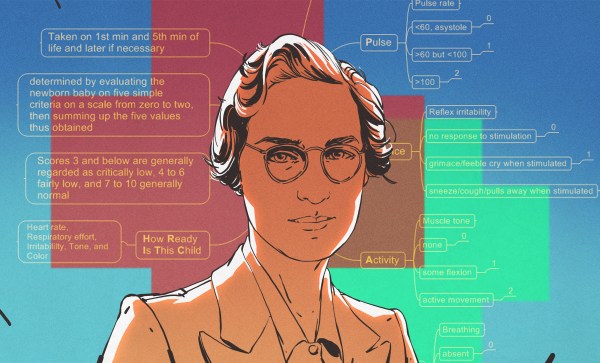

Virginia Apgar May Have Saved Your Life

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, something sort of strange happened in the United States. The infant mortality rate went into decline, but the number of babies that died within 24 hours of birth didn’t budge at all. It sounds terrible, but back then, many babies who weren’t breathing well or showed other signs of a failure to thrive were usually left to die and recorded as stillborn.

As an obstetrical anesthesiologist, physician, and medical researcher, Virginia Apgar was in a great position to observe fresh newborns and study the care given to them by doctors. She is best known for inventing the Apgar Score, which is is used to quickly rate the viability of newborn babies outside the uterus. Using the Apgar Score, a newborn is evaluated based on heart rate, reflex irritability, muscle tone, respiratory effort, and skin color and given a score between zero and two for each category. Depending on the score, the baby would be rated every five minutes to assess improvement. Virginia’s method is still used today, and has saved many babies from being declared stillborn.

Virginia wanted to be a doctor from a young age, specifically a surgeon. Despite having graduated fourth in her class from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Virginia was discouraged from becoming a surgeon by a chairman of surgery and encouraged to go to school a little bit longer and study anesthesiology instead. As unfortunate as that may be, she probably would have never have created the Apgar Score with a surgeon’s schedule. Continue reading “Virginia Apgar May Have Saved Your Life”

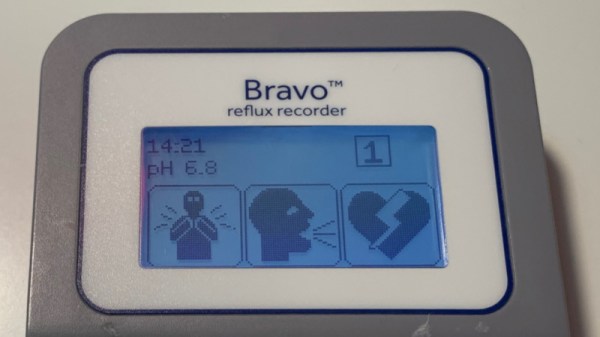

Tuning Into Medical Implants With The RTL-SDR

With a bit of luck, you’ll live your whole life without needing an implanted medical device. But if you do end up getting the news that your doctor will be installing an active transmitter inside your body, you might as well crack out the software defined radio (SDR) and see if you can’t decode its transmission like [James Wu] recently did.

Before the Medtronic Bravo Reflux Capsule was attached to his lower esophagus, [James] got a good look at a demo unit of the pencil-width gadget. Despite the medical technician telling him the device used a “Bluetooth-like” communications protocol to transmit his esophageal pH to a wearable receiver, the big 433 emblazoned on the hardware made him think it was worth taking a closer look at the documentation. Sure enough, its entry in the FCC database not only confirmed the radio transmitted a 433.92 MHz OOK-PWM encoded signal, but it even broke down the contents of each packet. If only it was always that easy, right?

Of course he still had to put this information into practice, so the next step was to craft a configuration file for the popular rtl_433 program which split each packet into its principle parts. This part of the write-up is particularly interesting for those who might be looking to pull data in from their own 433 MHz sensors, medical or otherwise

Unfortunately, there was still one piece of the puzzle missing. [James] knew which field was the pH value from the FCC database, but the 16-bit integer he was receiving didn’t make any sense. After some more research into the hardware, which uncovered another attempt at decoding the transmissions from the early days of the RTL-SDR project, he realized what he was actually seeing was the combination of two 8-bit pH measurements that are sent out simultaneously.

We were pleasantly surprised to see how much public information [James] was able to find about the Medtronic Bravo Reflux Capsule, but in a perfect world, this would be the norm. You deserve to know everything there is to know about a piece of electronics that’s going to be placed inside your body, but so far, the movement towards open hardware medical devices has struggled to gain much traction.

Adding A Gentle Touch To Prosthetic Limbs With Somatosensory Stimulation

When Nathan Copeland suffered a car accident in 2004, damage to his spinal cord at the C5/C6 level resulted in tetraplegic paralysis. This left him initially at the age of 18 years old to consider a life without the use of his arms or legs, until he got selected in 2014 for a study at the University of Pittsburgh involving the controlling of a robotic limb using nothing but one’s mind and a BCI.

While this approach, as replicated in various other studies, works well enough for simple tasks, it comes with the major caveat that while it’s possible to control this robotic limb, there is no feedback from it. Normally when we try to for example grab an object with our hand, we are aware of the motion of our arm and hand, until the moment when our fingers touch the object which we’re reaching for.

In the case of these robotic limbs, the only form of feedback was of the visual type, where the user had to look at the arm and correct its action based on the observation of its position. Obviously this is far from ideal, which is why Nathan hadn’t just been implanted with Utah arrays that read out his motor cortex, but also arrays which connected to his somatosensory cortex.

As covered in a paper by Flesher et al. in Nature, by stimulating the somatosensory cortex, Nathan has over the past few years regained a large part of the sensation in his arm and hand back, even if they’re now a robotic limb. This raises the question of how complicated this approach is, and whether we can expect it to become a common feature of prosthetic limbs before long. Continue reading “Adding A Gentle Touch To Prosthetic Limbs With Somatosensory Stimulation”

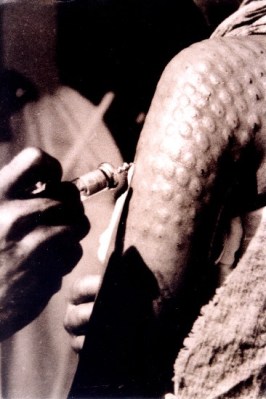

Alice Ball Steamrolled Leprosy

Leprosy is a bacterial disease that affects the skin, nerves, eyes, and mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract. It is transmitted via droplets and causes skin lesions and loss of sensation in these regions. Also known as Hansen’s disease after the 19th century scientist who discovered its bacterial origin, leprosy has been around since ancient times, and those afflicted have been stigmatized and outcast for just as long. For years, people were sent to live the rest of their days in leper colonies to avoid infecting others.

Until Alice Ball came along, the only thing that could be done for leprosy — injecting oil from the seeds of an Eastern evergreen tree — didn’t really do all that much to help. Eastern medicine has been using oil from the chaulmoogra tree since the 1300s to treat various maladies, including leprosy.

The problem is that although it somewhat effective, chaulmoogra oil is difficult to get it into the body. Ingesting it makes most people vomit. The stuff is too sticky to be applied topically to the skin, and injecting it causes the oil to clump in abscesses that make the patients’ skin look like bubble wrap.

In 1866, the Hawaiian government passed a law to quarantine people living with leprosy on the tiny island of Moloka’i. Every so often, a ferry left for the island and delivered these people to their eventual death. Most patients don’t die of leprosy, but from secondary infection or disease. By 1915, there were 1,100 people living on Moloka’i from all over the United States, and they were running out of room. Something had to be done.

Professor Alice Ball hacked the chemistry of chaulmoogra oil and made it less viscous so it could be easily injected. As a result, it was much more effective and remained the ideal treatment until the 1940s when sulfate antibiotics were discovered. So why haven’t you heard of Alice before? She died before she could publish her work, and then it was stolen by the president of her university. Now, over a century later, Alice is starting to get the recognition she deserves.