Losing a limb often means getting fitted for a prosthetic. Although there have been some scientific and engineering advances (compare a pirate’s peg leg to “blade runner” Oscar Pistorius’ legs), they still are just inert attachments to your body. Researchers at Johns Hopkins hope to change all that. In the Journal of Neural Engineering, they announced a proof of concept design that allowed a person to control prosthetic fingers using mind control.

Medical Hacks705 Articles

Brain Waves Can Answer Spock’s (and VR’s) Toughest Question

In Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, the usually unflappable Spock found himself stumped by one question: How do you feel? If researchers at the University of Memphis and IBM are correct, computers by Spock’s era might not have to ask. They’d know.

[Pouya Bashivan] and his colleagues used a relatively inexpensive EEG headset and machine learning techniques to determine if, with limited hardware, the computer could derive a subject’s mental state. This has several potential applications including adapting virtual reality avatars to match the user’s mood. A more practical application might be an alarm that alerts a drowsy driver.

Continue reading “Brain Waves Can Answer Spock’s (and VR’s) Toughest Question”

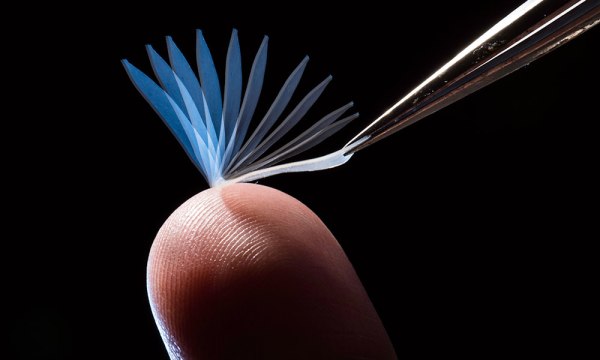

New Shape-Shifting Polymer Works Hard, Plays Hard

A research group at the University of Rochester has developed a new polymer with some amazing traits. It can be stretched or manipulated into new shapes, and it will hold that shape until heat is applied. Shape-shifting polymers like this already exist, but this one is special: it can go back to its original shape when triggered by the heat of a human body. Oh, and it can also lift objects up to 1000 times its mass.

The group’s leader, chemical engineering professor [Mitch Anthamatten], is excited by the possibilities of this creation. When the material is stretched, strain is induced which deforms the chains and triggers crystallization. This crystallization is what makes it retain the new shape. Once heat is applied, the crystals are broken and the polymer returns to its original shape. These properties imply several biomedical applications like sutures and artificial skin. It could also be used for tailored-fit clothing or wearable technology.

The shape-shifting process creates elastic energy in the polymer, which means that it can do work while it springs back to normal. Careful application of molecular linkers made it possible for the group to dial in the so-called melting point at which the crystallization begins to break down. [Anthamatten] explains the special attributes of the material in one of the videos after the break. Another video shows examples of some of the work-related applications for the polymer—a stretched out strand can pull a toy truck up an incline or crush a dried seed pod.

Continue reading “New Shape-Shifting Polymer Works Hard, Plays Hard”

Hacking Hearing With A Bone Conduction Bluetooth Speaker

When a hacker finds himself with a metal disc and magnet surgically implanted in his skull, chances are pretty good that something interesting will come from it. [Eric Cherry]’s implant, designed to anchor a bone-conduction hear aid, turned out to be a great place to mount a low-cost Bluetooth speaker for his phone – at least when he’s not storing paperclips behind his ear.

With single-sided deafness, [Eric]’s implant allows him to attach his bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA), which actually uses the skull itself as a resonator to bypass the outer ear canal and the bones of the middle ear and send vibrations directly to the cochlea. As you can imagine, a BAHA device is a pretty pricey bit of gear, and being held on by just a magnet can be tense in some situations. [Eric] decided to hack a tiny Bluetooth speaker to attach to his implant and see if it would work with his phone. A quick teardown and replacement of the stock speaker with a bone-conduction transducer from Adafruit took care of the electronics, which were installed in a 3D printed enclosure compatible with the implant. After pairing with his phone he found that sound quality was more than good enough to enjoy music without risking his implant. And all for only $22 out-of-pocket. While only a Bluetooth speaker in its current form, we can see how the microphone in the speakerphone might be used to build a complete hearing aid on the cheap.

We think this is a great hack that really opens up some possibilities for the hearing impaired. Of course it’s not suitable for all types of hearing loss; for more traditional hearing aid users, this Bluetooth-enabled adapter might be a better choice for listening to music.

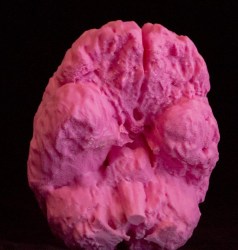

This Is My 3D Printed Brain!

This hack is a strange mixture of awesome and ghoulish. [Andrew Sink] created a 3D printed version of his brain. He received a CD from an MRI session that contained the data obtained by the scan. Not knowing what to do with it he created a model of his brain.

Out of a number of images, some missing various parts of his head, he selected the one that was most complete. This image he brought into OisriX, a Mac program for handling DICOM files. He worked on the image for an hour dissecting away his own eyes, skull, and skin. An STL file containing his brain was brought over to NetFabb to see how it looked. There was still more dissection needed so [Andrew] turned to Blender. More bits and pieces of his skull’s anatomy were dissected to pare it down to just the brain. But there were some lesions at the base of the brain that needed to be filled. With the help of [Cindy Raggio] these were filled in to complete the 3D image.

The usual steps sent it to the 3D printer to be produced at 0.2 mm resolution. It only took 49 hours to print at full-size. This brain was printed for fun, but we’ve seen other 3D printed brain hacks which were used to save lives. How many people do you know that have a spare brain sitting around?

Augmented Reality Ultrasound

Think of Virtual Reality and it’s mostly fun and games that come to mind. But there’s a lot of useful, real world applications that will soon open up exciting possibilities in areas such as medicine, for example. [Victor] from the Shackspace hacker space in Stuttgart built an Augmented Reality Ultrasound scanning application to demonstrate such possibilities.

But first off, we cannot get over how it’s possible to go dumpster diving and return with a functional ultrasound machine! That’s what member [Alf] turned up with one day. After some initial excitement at its novelty, it was relegated to a corner gathering dust. When [Victor] spotted it, he asked to borrow it for a project. Shackspace were happy to donate it to him and free up some space. Some time later, [Victor] showed off what he did with the ultrasound machine.

As soon as the ultrasound scanner registers with the VR app, possibly using the image taped to the scan sensor, the scanner data is projected virtually under the echo sensor. There isn’t much detail of how he did it, but it was done using Vuforia SDK which helps build applications for mobile devices and digital eye wear in conjunction with the Unity 5 cross-platform game engine. Check out the video to see it in action.

Thanks to [hadez] for sending in this link.

Baby Saved By Doctors Using Google Cardboard After 3D Printer Fails

It’s a parent’s worst nightmare. Doctors tell you that your baby is sick and there’s nothing they can do. Luckily though, a combination of hacks led to a happy ending for [Teegan Lexcen] and her family.

When [Cassidy and Chad Lexcen]’s twin daughters were born in August, smaller twin [Teegan] was clearly in trouble. Diagnostics at the Minnesota hospital confirmed that she had been born with only one lung and half a heart. [Teegan]’s parents went home and prepared for the inevitable, but after two months, she was still alive. [Cassidy and Chad] started looking for second opinions, and after a few false starts, [Teegan]’s scans ended up at Miami’s Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, where the cardiac team looked them over. They ordered a 3D print of the scans to help visualize possible surgical fixes, but the 3D printer broke.

Not giving up, they threw [Teegan]’s scans into Sketchfab, slapped an iPhone into a Google Cardboard that one of the docs had been playing with in his office, and were able to see a surgical solution to [Teegan]’s problem. Not only was Cardboard able to make up for the wonky 3D printer, it was able to surpass it – the 3D print would only have been the of the heart, while the VR images showed the heart in the context of the rest of the thoracic cavity.[Dr. Redmond Burke] and his team were able to fix [Teegan]’s heart in early December, and she should be able to go home in a few weeks to join her sister [Riley] and make a complete recovery.

We love the effect that creative use of technology can have on our lives. We’ve already seen a husband using the same Sketchfab tool to find a neurologist that remove his wife’s brain tumor. Now this is a great example of doctors doing what it takes to better leverage the data at their disposal to make important decisions.