Writing out a few thousand words is easy. Getting them in the proper order, now that’s another story entirely. Sometimes you’ll find yourself staring at a blank page, struggling to sieve coherent thoughts from the screaming maelstrom swirling around in your head, for far longer than you’d care to admit. Or so we’ve heard, anyway.

Unfortunately, there’s no cure for writer’s block. But many people find that limiting outside distractions helps to keep the mental gears turning, which is why [Un Kyu Lee] has been working on a series of specialized writing devices. The latest version of the Micro Journal, powered by the ESP32, goes a long way towards achieving his goals of an instant-on electronic notebook.

The writing experience on the Micro Journal is unencumbered by the normal distractions you’d have on a computer or mobile device, as the device literally can’t do anything but take user input and save it as a text file. We suppose you could achieve similar results with a pen and a piece of paper…but where’s the fun in that? These devices are more widely known as writerdecks, which is an extension of the popular cyberdeck concept of hyper-personalized computers.

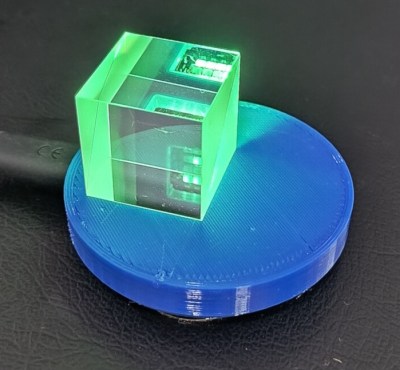

This newest Micro Journal, which is the fourth iteration of the concept for anyone keeping score, packs a handwired 30% ortholinear keyboard, a 2.8″ ILI9341 240×320 LCD (with SD card slot), ESP32 dev board, and an 18650 battery with associated charging board into a minimalist 3D printed enclosure.

This newest Micro Journal, which is the fourth iteration of the concept for anyone keeping score, packs a handwired 30% ortholinear keyboard, a 2.8″ ILI9341 240×320 LCD (with SD card slot), ESP32 dev board, and an 18650 battery with associated charging board into a minimalist 3D printed enclosure.

Unable to find any suitable firmware to run on the device, [Un Kyu Lee] has developed his own open source text editor to run on the WiFi-enabled microcontroller. While the distraction-free nature of the Micro Journal naturally means the text editor itself is pretty spartan in terms of features, it does allow syncing files with Google Drive — making it exceptionally easy to access your distilled brilliance from the comfort of your primary computing device.

While the earlier versions of the Micro Journal were impressive in their own way, we really love the stripped down nature of this ESP32 version. It reminds us a bit of the keezyboost40 and the EdgeProMX, both of which were entered into the 2022 Cyberdeck Contest.

Continue reading “ESP32 Provides Distraction-Free Writing Experience”