Most drinkbots are complicated—some intentionally so, others seemingly by design necessity. If you have a bunch of bottles of booze you still need a way to get it out of the bottles in a controlled fashion, usually through motorized pouring or pumping. Sometimes all thoe tubes and motors and wires looks really cool and sci fi. Still, there’s nothing wrong with a really clean design.

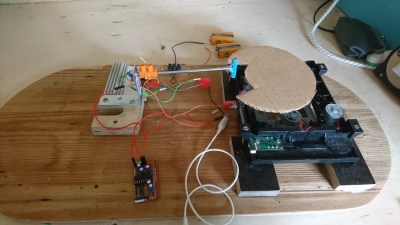

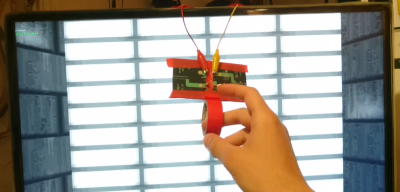

[Lukas Šidlauskas’s] Open Source Barbot project uses only two motors to actuate nine bottles using only a NEMA-17 stepper to move the tray down along the length of the console and a high-torque servo to trigger the Beaumont Metrix SL spirit measures. These barman’s bottle toppers dispense 50 ml when the button is pressed, making them (along with gravity) the perfect way to elegantly manage so many bottles. Drink selection takes place on an app, connected via Bluetooth to the Arduino Mega running the show.

The Barbot is an Open Source project with project files available from [Lukas]’s GitHub repository

and discussions taking place in a Slack group.

If it’s barbots you’re after, check out this Synergizer 4-drink barbot and the web-connected barbot we published a while back.