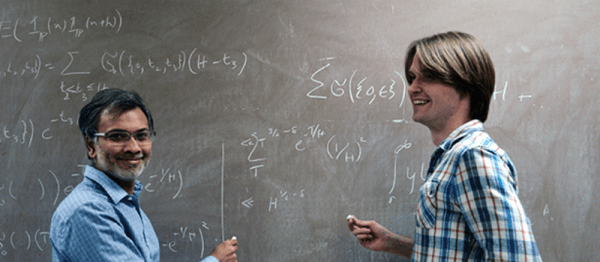

If you’ve spent any time around prime numbers, you know they’re a pretty odd bunch. (Get it?) But it turns out that they’re even stranger than we knew — until recently. According to this very readable writeup of brand-new research by [Kannan Soundararajan] and [Robert Lemkein], the final digits of prime numbers repel each other.

More straightforwardly stated, if you pick any given prime number, the last digit of the next-largest prime number is disproportionately unlikely to match the final digit of your prime. Even stranger, they seem to have preferences. For instance, if your prime ends in 3, it’s more likely that the next prime will end in 9 than in 1 or 7. Whoah!

Even spookier? The finding holds up in many different bases. It was actually first noticed in base-three. The original paper is up on Arxiv, so go check it out.

This is a brand-new finding that’s been hiding under people’s noses essentially forever. The going assumption was that primes were distributed essentially randomly, and now we have empirical evidence that it’s not true. What this means for cryptology or mathematics? Nobody knows, yet. Anyone up for wild speculation? That’s what the comments section is for.

(Headline photo of researchers Kannan Soundararajan and Robert Lemke: Waheeda Khalfan)

![You're still better at Ms. Pacman [Source: DeepMind paper in Nature]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/deepmind-atari2600-machine-learning.jpg?w=496)