Most video game manufacturers aren’t too keen on homebrew games, or people trying to get more utility out of a video game system than it was designed to have. While some effort is made to keep people from slapping a modchip on an Xbox or from running an emulator for a Playstation, it’s almost completely impossible to stop some of the hardware hacking that is common on older cartridge-based games. The only limit is usually the cost of an EPROM programmer, but [Robson] has that covered now with his Arduino-based SNES EPROM programmer.

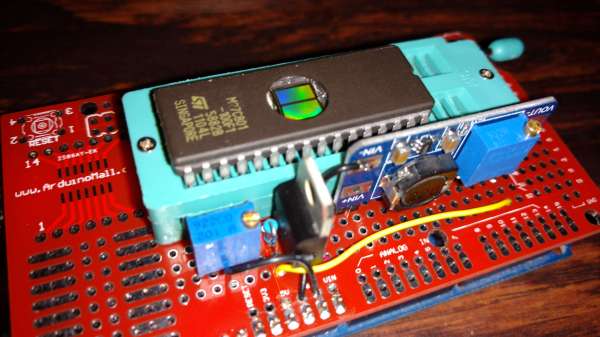

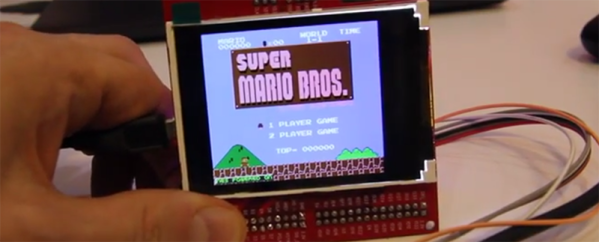

Normally this type of hack involves finding any cartridge for the SNES at the lowest possible value, burning an EPROM with the game that you really want, and then swapping the new programmed memory with the one in the worthless cartridge. Even though most programmers are pricey, it’s actually not that difficult to write bits to this type of memory. [Robson] runs us through all of the steps to get an Arduino set up to program these types of memory, and then puts it all together into a Super Nintendo where it looks exactly like the real thing.

If you don’t have an SNES lying around, it’s possible to perform a similar end-around on a Sega Genesis as well. And, if you’re more youthful than those of us that grew up in the 16-bit era, there’s a pretty decent homebrew community that has sprung up around the Nintendo DS and 3DS, too.

Thanks to [Rafael] for the tip!