One of the most difficult user interfaces to get right is video editing. It is complex and fiddly with large amounts of precision required even after four or five hours of straight editing. Seeking to bring some of that interface out into the real world, [Zack Freedman] built a mechanical video editing keyboard.

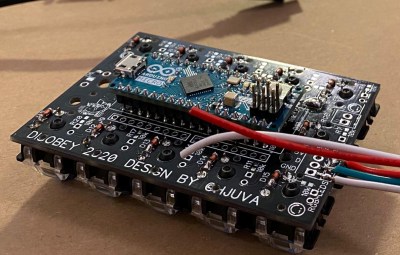

The keyboard in question features popular shortcuts and keys to breeze through different parts of editing. The biggest feature is, of course, the large scrubbing knob, allowing [Zack] to fly through long video with precision. We’ve seen our fair share of mechanical keyboards that aren’t traditional keyboards on Hackaday before, such as this number pad or this macro pad.

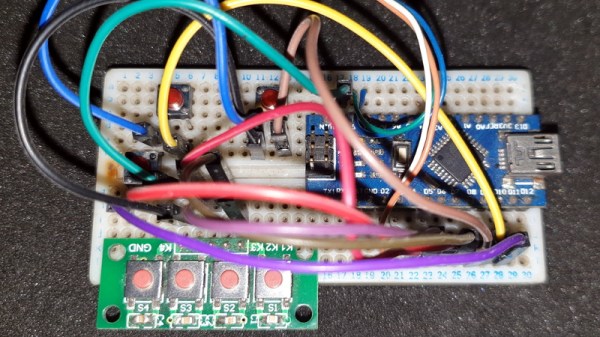

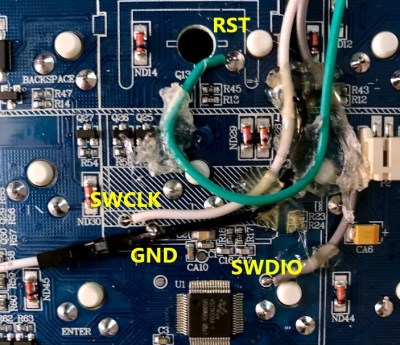

One of the unique constraints of this project was the fact that Zack had a deadline of two days. This self-imposed deadline was to help focus the work and drive it towards completion. This meant that it had to be designed in such a way that roadblocks or troublesome features could be designed around or cut out altogether. At its heart, this project is just 14 mechanical switches, 4 potentiometers, and a Teensy to drive it all. It is the design, prototyping, and thought that went into this project that makes it noteworthy. There are plenty of lessons here about how to manage a project’s timeline and advice about how to actually finish it.

Code, STL’s, diagrams, and instructions are all on his GitHub.

Continue reading “Spin The Video Track With A Mechanical Flair”