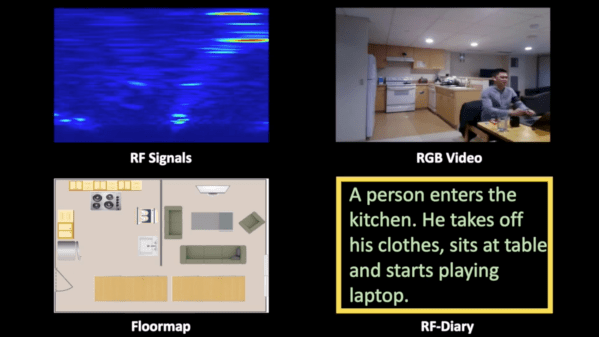

Caring for the elderly and vulnerable people while preserving their privacy and independence is a challenging proposition. Reaching a panic button or calling for help may not be possible in an emergency, but constant supervision or camera surveillance is often neither practical nor considerate. Researchers from MIT CSAIL have been working on this problem for a few years and have come up with a possible solution called RF Diary. Using RF signals, a floor plan, and machine learning it can recognize activities and emergencies, through obstacles and in the dark. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it builds on previous research by CSAIL.

The RF system used is effectively frequency-modulated continuous-wave (FMCW) radar, which sweeps across the 5.4-7.2 GHz RF spectrum. The limited resolution of the RF system does not allow for the recognition of most objects, so a floor plan gives information on the size and location of specific features like rooms, beds, tables, sinks, etc. This information helps the machine learning model recognize activities within the context of the surroundings. Effectively training an activity captioning model requires thousands of training examples, which is currently not available for RF radar. However, there are massive video data sets available, so researchers employed a “multi-modal feature alignment training strategy” which allowed them to use video data sets to refine their RF activity captioning model.

There are still some privacy concerns with this solution, but the researchers did propose some improvements. One interesting idea is for the monitored person to give an “activation” signal by performing a specified set of activities in sequence.