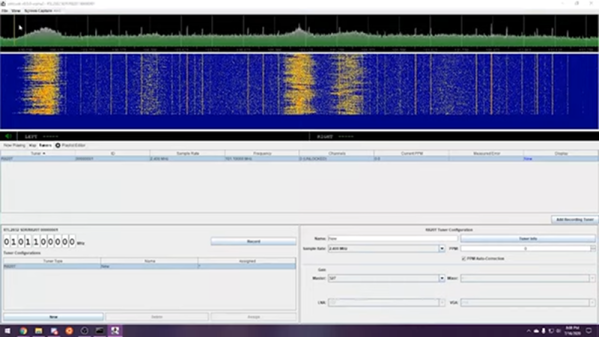

Perhaps it’s just one of those things adults dream up to entertain their children, but were you ever told to count slowly the time between seeing a lightning flash and hearing the rumble of thunder? The idea was that the count would tell you how far away the storm was, but from a grown-up perspective the calibration accuracy of a child saying “one… two…three…” in miles seems highly suspect. It’s a valid technique though, and it can be used to monitor thunderstorms by the radio emissions created through the electrical discharge. It’s an area the SAGE project has been working in, and they’ve posted some details including a fascinating run-down of the software techniques , on how lightning can be detected with an RTL-SDR.

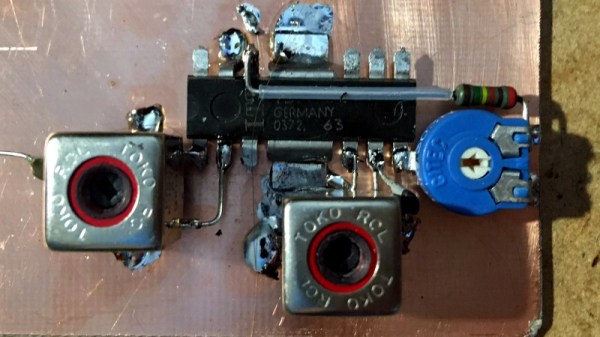

A lightning strike produces a characteristic wideband burst that shows up in the time domain as a maximum point that can easily be detected but could also be confused with radio interference from another source. Thus after identifying maxima they zoom in and perform a Fourier transform to spot the wideband burst. It’s all done in Python, and the pleasant surprise is how straightforward to understand it all is.

SAGE are working on a distributed sensor network, so we hope this work might one day give us real-time open lightning data. The FFT approach should ensure that it won’t be fooled by false positives as a traditional detector might be.

Via RTL-SDR.com.