We’re knee-deep in new microcontrollers over here, from the new Raspberry Pi Pico to an engineering sample from Espressif that’s right now on our desk. (Spoiler alert, review coming out Monday.) And microcontroller peripherals are a little bit like Pokemon — you’ve just got to catch them all. If a microcontroller doesn’t have 23 UARTS, WiFi, Bluetooth, IR/DA, and a 16-channel 48 MHz ADC, it’s hardly worth considering. More is always better, right?

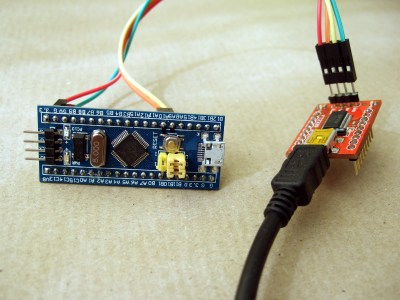

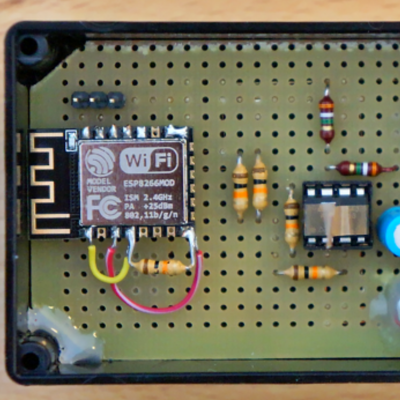

No, it’s not. Chip design is always a compromise, and who says you’re limited to one microcontroller per project anyway? [Francesco] built a gas-meter reader that reminded to think outside of the single-microcontroller design paradigm. It uses an ATtiny13 for its low power sleep mode, ease of wakeup, and decent ADCs. Pairing this with an ESP8266 that’s turned off except when the ATtiny wants to send data to the network results in a lower power budget than would be achievable with the ESP alone, but still gets his data up into his home-grown cloud.

No, it’s not. Chip design is always a compromise, and who says you’re limited to one microcontroller per project anyway? [Francesco] built a gas-meter reader that reminded to think outside of the single-microcontroller design paradigm. It uses an ATtiny13 for its low power sleep mode, ease of wakeup, and decent ADCs. Pairing this with an ESP8266 that’s turned off except when the ATtiny wants to send data to the network results in a lower power budget than would be achievable with the ESP alone, but still gets his data up into his home-grown cloud.

Of course, there’s more complexity here than a single-micro solution, but the I2C lines between the two chips actually form a natural division of work — each unit can be tested separately. And it’s using each chip for what it’s best at: simple, low-power tasks for the Tiny and wrangling WiFi on the ESP.

Once you’ve moved past the “more is better” mindset, you’ll start to make a mental map of which chips are best for what. The obvious next step is combination designs like this one.