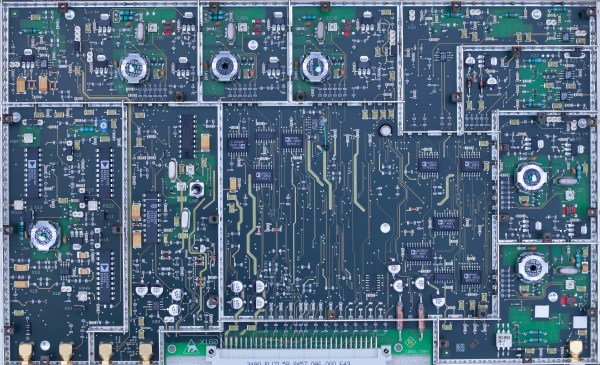

A right-to-repair battle is being waged in courts. The results of it, we might not see for a decade. The Caps Wiki is a project tackling our repairability problem from the opposite end – making it easy to share information with anyone who wants to repair something. Started by [Shelby], it’s heavily inspired by his vintage tech repairs experience that he’s been sharing for years on the [Tech Tangents] YouTube channel.

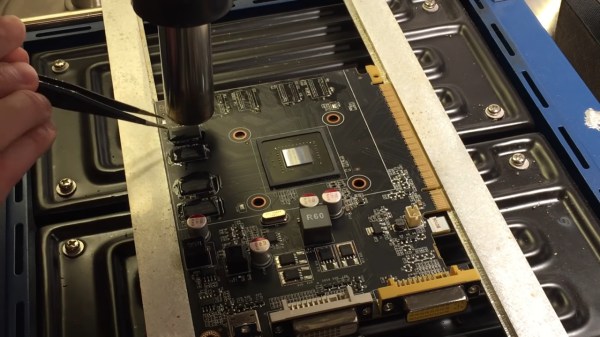

When repairing a device, there are many unknowns. How to disassemble it? What are the safety precautions? Which replacement parts should you get? A sporadic assortment of YouTube videos, iFixit pages and forum posts might help you here, but you have to dig them up and, often, meticulously look for the specific information that you’re missing.

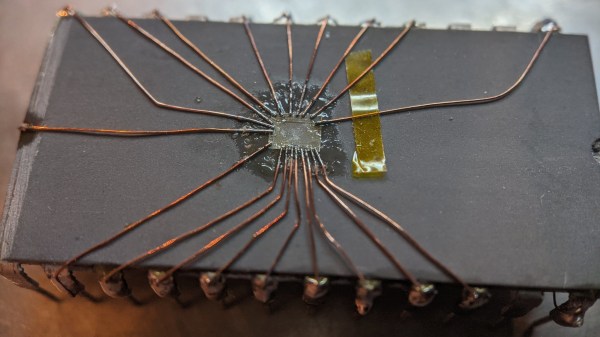

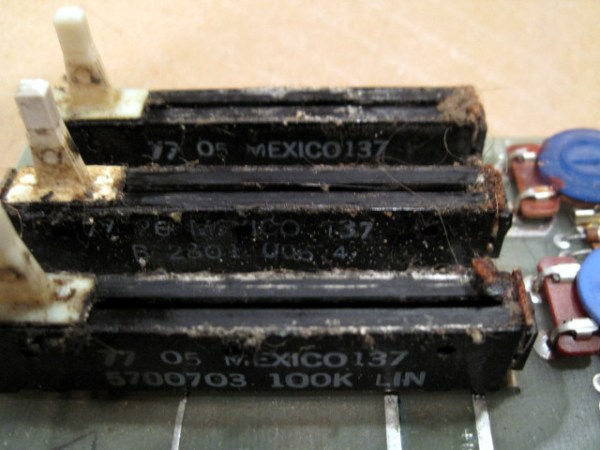

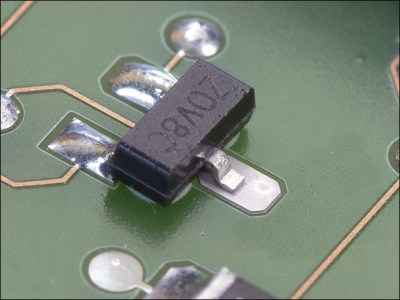

The Caps Wiki talks a lot about capacitor replacement repairs – but not just that. Any device, even modern ones, deserves a place on the Caps Wiki, only named like this because capacitor repairs are such a staple of vintage device repair. You could make a few notes about something you’re fixing, and have them serve as help and guideline for newcomers. With time, this won’t just become a valuable resource for quick repairs and old tech revival, but also a treasure trove of datapoints, letting us do research like “which capacitors brands or models tend to pass away prematurely”. Plus, it also talks about topics like mains-powered device repair safety or capacitor nuances!

Continue reading “Caps Wiki: Place For You To Share Your Repair Notes”