Want to see a 90s-era Acorn Archimedes A3020 home computer get opened up, refurbished, and taken for a test drive? Don’t miss [drygol]’s great writeup on Retrohax, because it’s got all that, and more!

The Archimedes was a line of ARM-based personal computers by Acorn Computers, released in the late 80s and discontinued in the 90s as Macintosh and IBM PC-compatible machines ultimately dominated. They were capable machines for their time, and [drygol] refurbished an original back into working order while installing a few upgrades at the same time.

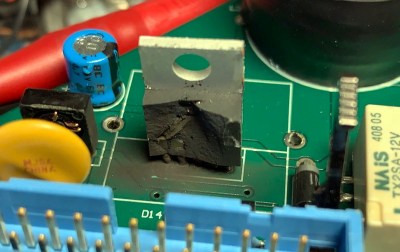

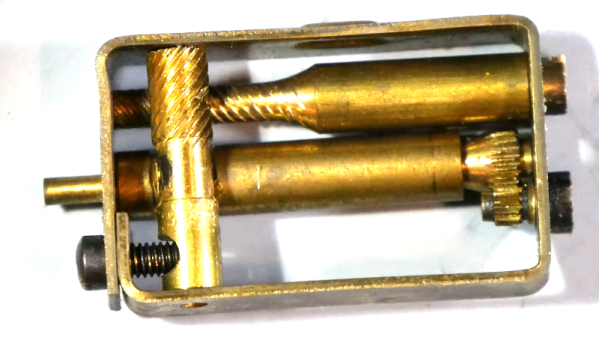

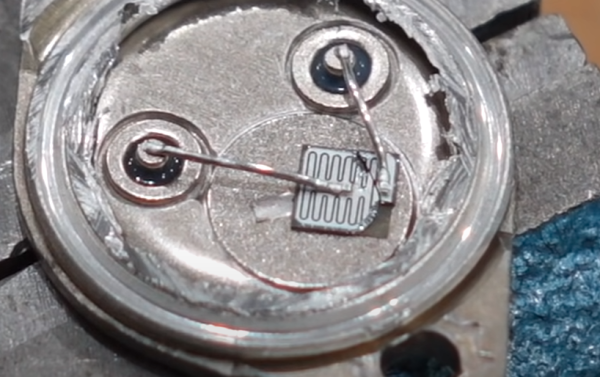

The first order of business was to open the machine up and inspect the internals. Visible corrosion gets cleaned up with oxalic acid, old electrolytic capacitors are replaced as a matter of course, and any corroded traces get careful repair. Removing corrosion from sockets requires desoldering the part for cleaning then re-soldering, so this whole process can be a lot of work. Fortunately, vintage hardware was often designed with hand-assembly in mind, so parts tend to be accessible for servicing with decent visibility in the process. The keyboard was entirely disassembled and de-yellowed, yielding an eye-poppingly attractive result.

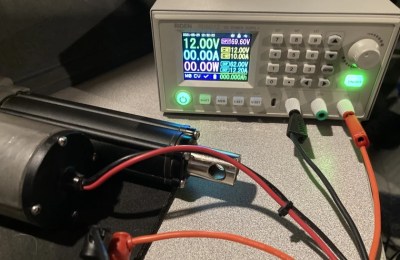

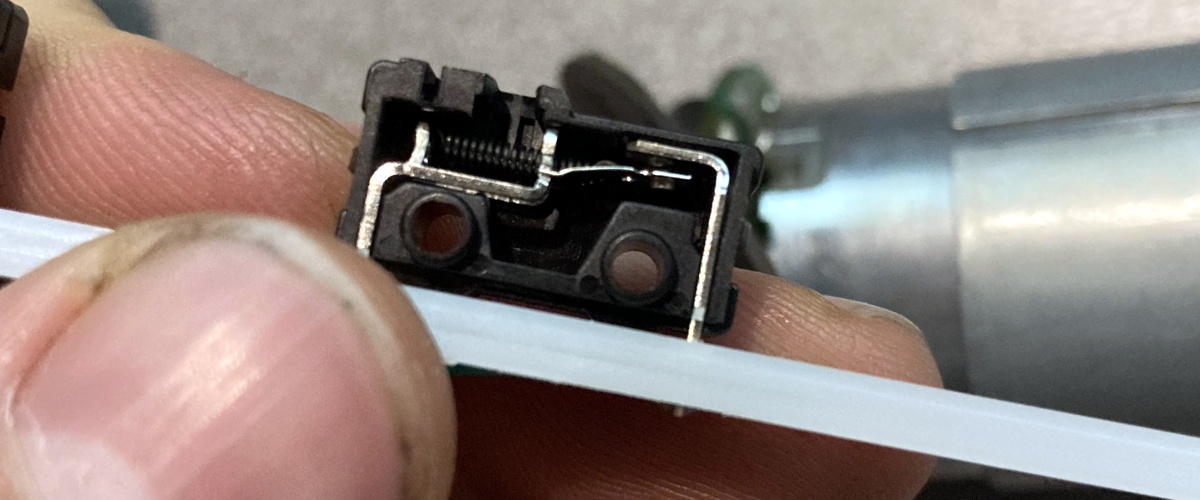

Once the computer itself was working properly, it was time for a few modern upgrades. One was to give the machine an adapter to use a CF card in place of an internal IDE hard drive, and [drygol] did a great job of using a 3D-printed piece to make the CF2IDE adapter look like a factory offering. The internal floppy drive was also replaced with a GOTEK floppy emulator (also with a 3D-printed adapter) for another modern upgrade.

The fully refurbished and upgraded machine looks slick, so watch the Acorn Archimedes A3020 show off what it can do in the video (embedded below), and maybe feel a bit of nostalgia.

Continue reading “See Acorn Archimedes Get Repaired And Refurbished, In Glorious Detail”