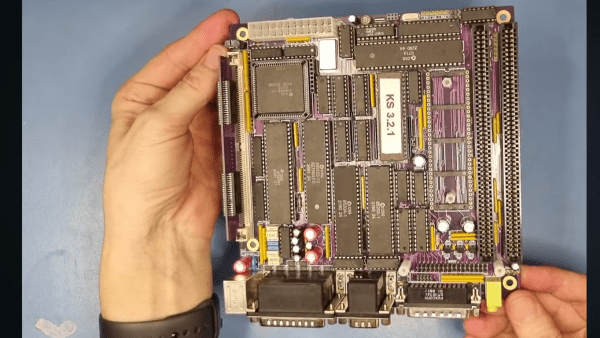

The Intel 8088 is an interesting chip, being a variant of the more well-known 8086. Given the latter went on to lend its designation to one of the world’s favorite architectures, you can tell which of the two was higher status. Regardless, it was the 8088 that lived in the first IBM PC, and now, it even has its own open-source BIOS.

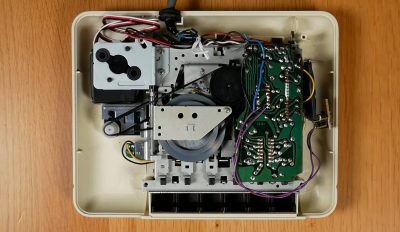

As with any BIOS, or Basic Input Output System, it’s charged with handling core low-level features for computers like the Micro 8088, Xi 8088, and NuXT. It handles chipset identification, keyboard and mouse communication, real-time clock, and display initialization, among other things.

Of course, BIOSes for 8088-based machines already exist. However, in many cases, they are considered to be proprietary code that cannot be freely shared over the internet. For retrocomputing enthusiasts, it’s of great value to have a open-source BIOS that can be shared, modified, and tweaked as needed to suit a wide variety of end uses.

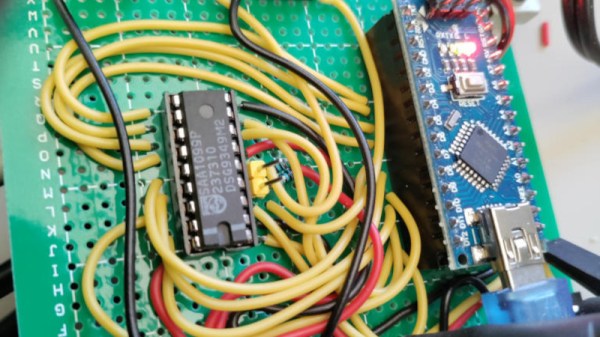

If you want to learn more about the 8088 CPU, we’ve looked in depth at that topic before. Feel free to drop us a line with your own retro Intel hacks if you’ve got them kicking around!