Although neutrinos are exceedingly common, their near-massless configuration means that their presence is rather ephemeral. Despite billions of them radiating every second towards Earth from sources like our Sun, most of them zip through our bodies and this very planet without ever interacting with either. This property is also what makes studying these particles that are so fundamental to our understanding so complicated. Fortunately recently published results by researchers behind the SNO+ neutrino detector project shows that we may see a significant bump in our neutrino detection sensitivity.

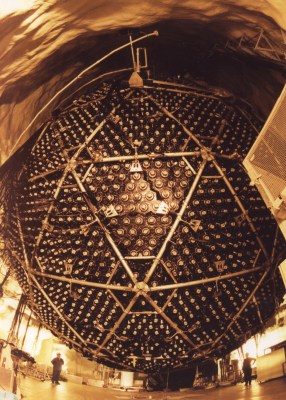

In their paper (preprint) in APS Physical Review Letters, the researchers describe how during the initial run of the new SNO+ neutrino detector they were able to detect anti-neutrinos originating from nuclear fission reactors over 240 kilometers away, including Canadian CANDU and US LWR types. This demonstrated the low detection threshold of the SNO+ detector even in its still incomplete state between 2017 and 2019. Filled with just heavy water and during the second run with the addition of nitrogen to keep out radioactive radon gas from the surrounding rock of the deep mine shaft, SNO+ as a Cherenkov detector accomplished a threshold of 1.4 MeV at its core, more than sufficient to detect the 2.2 MeV gamma radiation from the inverse beta decays (IBD) that the detector is set up for.

The SNO+ detector is the evolution of the original Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO), located 2.1 km below the surface in the Creighton Mine. SNO ran from 1999 to 2006, and was part of the effort to solve the solar neutrino problem, which ultimately revealed the shifting nature of neutrinos via neutrino oscillation. Once fully filled with 780 tons of linear alkylbenzene as a scintillator, SNO+ will investigate a number of topics, including neutrinoless double beta decay (Majorana fermion), specifically the confounding question regarding whether neutrinos are its own antiparticle or not

The focus of SNO+ on nearby nuclear fission reactors is due to the constant beta decay that occurs in their nuclear fuel, which not only produces a lot of electron anti-neutrinos. This production happens in a very predictable manner due to the careful composition of nuclear fuel. As the researchers noted in their paper, SNO+ is accurate enough to detect when a specific reactor is due for refueling, on account of its change in anti-neutrino emissions. This is a property that does not however affect Canadian CANDU PHWRs, as these are constantly refueled, making their neutrino production highly constant.

Each experiment by SNO+ produces immense amounts of data (hundreds of terabytes per year) that takes a while to process, but if these early results are anything to judge by, then SNO+ may progress neutrino research as much as SNO and kin have previously.