[Max Woolf] sometimes struggles to create ideal headlines for his blog posts, and decided to apply his experience with machine learning to the problem. He asked: could an AI be trained to optimize his blog titles? It is a fascinating application of natural language processing, and [Max] explains all about what it does and how it works.

The machine learning framework [Max] uses is GPT-3, a language model that works with natural-seeming human language that is capable of being tweaked in different ways. [Max] uses OpenAI’s GPT-3 API (which, by the way, is much easier to experiment with than one might think) and here is the basic workflow for his title optimizer:

- The optimizer takes as input a blog post title to optimize.

- OpenAI’s pre-trained GPT-3 engine is used to generate six alternate titles.

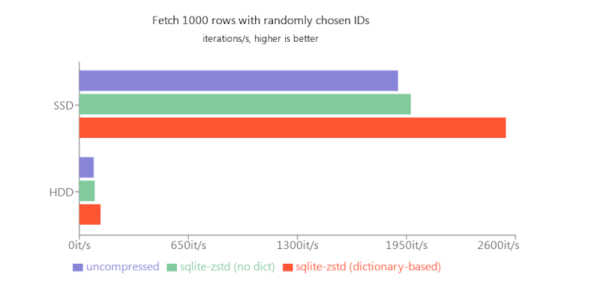

- For each of those alternate titles, a fine-tuned version of GPT-3 is consulted to judge how “good” they are based on custom training data. (“Good” in this context means “similar to titles of successful submissions on Hacker News“, but more on that in a moment.)

- Print the results.

Continue reading “Blog Title Optimizer Uses AI, But How Well Does It Work?”