A big part of the Hackaday Prize this year is robotics modules, and already we’ve seen a lot of projects adding intelligence to motors. Whether that’s current sensing, RPM feedback, PID control, or adding an encoder, motors are getting smart. Usually, though, we’re talking about fancy brushless motors or steppers. The humble DC brushed motor is again left out in the cold.

This project is aiming to fix that. It’s a smart motor driver for dumb DC brushed motors. You know, the motors you can buy for pennies. The motors that are the cheapest way to add movement to any project. Those motors.

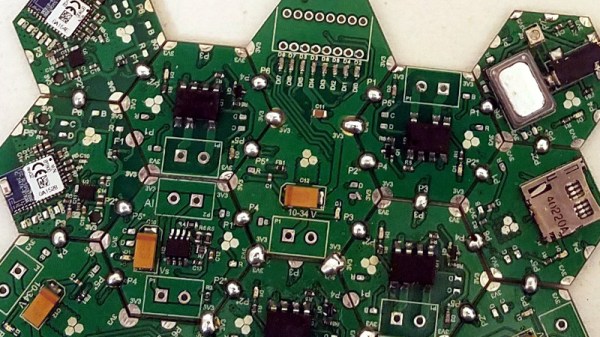

The Smart Motor Driver for Robotics allows a DC brushed motor to be controlled by a host microcontroller over I2C, and sends back the speed and direction of the motor. PID is implemented, and the motor can maintain its own speed, independently of a lot of difficult control on the host system.

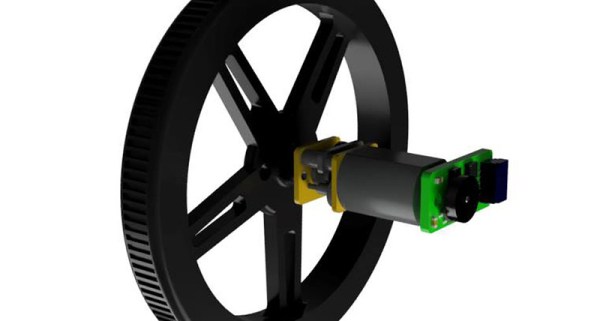

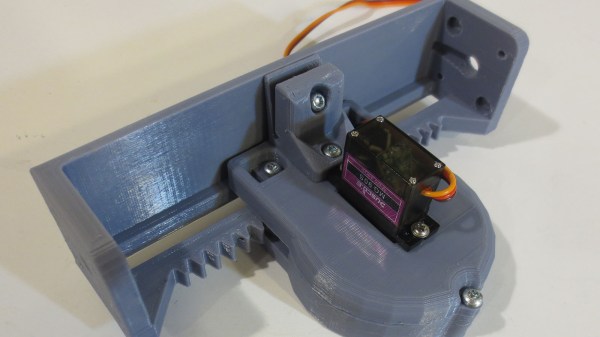

The guts of this motor controller are made of a PIC 12F microcontroller, a H-bridge motor driver, a Hall-effect sensor, and a neat magnetic encoder disc. Ultimately, this project will simply bolt onto the back of a cheap brushed motor and give it the same capabilities as a fancy servo or stepper. It’s never going to have the same torque or power handling as a beefy NEMA 17 stepper, but sometimes you don’t need that, and a simple brushed motor will do. A great project, and an excellent entry for the Hackaday Prize.