We don’t have to tell you that the representation hackers and makers get in popular media is usually pretty poor. At this point, we’ve all come to accept that Hollywood is only interested in perpetuating negative stereotypes about hackers. But in scenes where the plot calls for a character to be working on an electronic device, it often seems like the prop department just sticks a soldering iron in the actor’s hand and calls it a day.

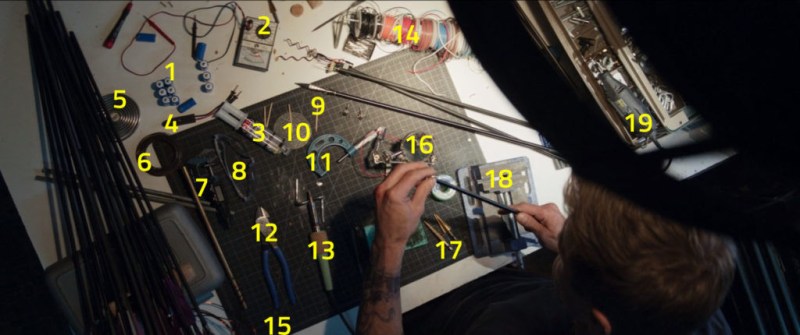

Of course, there are some exceptions. In the final episode of Marvel’s Hawkeye, the titular character is shown building some custom gear in a work area that looks suspiciously like somewhere actual work might get done. The set design was impressive enough that [Giovanni Bernardo] decided to pause the show and try to identify some of the tools and gadgets that litter the character’s refreshingly chaotic bench.

Now to be clear, we haven’t personally seen the latest Marvel spectacle from the House of Mouse, and it’s entirely possible that the illusion falls apart when taken as a whole. But from what we’re seeing here, it certainly looks like whoever did the set dressing for Hawkeye seems to have made an effort to recreate the hackerspace chic. We’ve got a multimeter within arm’s reach, the classic magnifying glass third arm, a Wiha screwdriver about to roll out of frame, and even some JB-Weld. If this looks eerily like what’s currently on your own bench, don’t worry, you’re not alone.

On the wider shot, we can see that the attention to detail wasn’t limited to the close-up. From the tools hanging on the pegboard to the shelves filled with rows of neatly labeled bins, we totally buy this as a functional workspace. It’s quite a bit neater than where we currently do our tinkering, but that’s more of a personal problem than anything. As we’ve seen, there are certainly people in this community who take their organization seriously.

Portrayals of science or technology in the media often leave a lot to be desired, which is why it’s so important to praise productions that put in the effort to get things right. With a little luck, maybe it will get through to the right people and raise the bar a bit. But even if it doesn’t change anything, we can at least give the folks behind the scenes some well-deserved recognition.

Using a shop vac is fine at smaller scales, but they can quickly be filled up on bigger jobs. To stop it getting filled up as quickly and wasting vacuum bags, [rctestflight] wanted to build a 3D-printed cyclonic separator to catch and dump the heavier-than-air particles from the routing process into an attached bucket.

Using a shop vac is fine at smaller scales, but they can quickly be filled up on bigger jobs. To stop it getting filled up as quickly and wasting vacuum bags, [rctestflight] wanted to build a 3D-printed cyclonic separator to catch and dump the heavier-than-air particles from the routing process into an attached bucket.