Depending on the circumstances you find yourself in, a Geiger counter can be a tremendously useful tool. With just a click or a chirp, it can tell you if any invisible threats lurk. But a Geiger counter is a “yes or no” instrument; it can only tell you if an ionizing event occurred, revealing nothing about the energy of the radiation. For that, you need something like this gamma-ray spectroscope.

Dubbed the Pomelo by [mihai.cuciuc], the detector is a homebrew solid-state scintillation counter made from a thallium-doped cesium iodide crystal and a silicon photomultiplier. The scintillator is potted in silicone in a 3D printed enclosure, to protect the hygroscopic crystal from both humidity and light. There’s also a temperature sensor on the detector board for thermal compensation. The Pomelo Core board interfaces with the physics package and takes care of pulse shaping and peak detection, while a separate Pomelo Zest board has an ESP32-C6, a small LCD and buttons for UI, SD card and USB interfaces, and an 18650 power supply. Plus a piezo speaker, because a spectroscope needs clicks, too.

The ability to determine the energy of incident photons is the real kicker here, though. Pomelo can detect energies from 50 keV all the way up to 3 MeV, and display them as graphs using linear or log scales. The short video below shows the Pomelo in use on samples of radioactive americium and thorium, showing different spectra for each.

[mihai.cuciuc] took inspiration for the Pomelo from this DIY spectrometer as well as the CosmicPi.

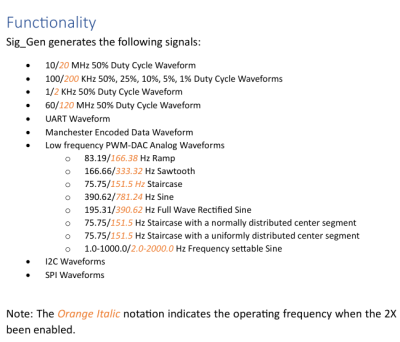

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.