Necessity is the mother of invention, but cheap crap from China is the mother of reverse engineering. [Michael] found a very, very cheap toy quadcopter in his local shop, and issued a challenge to himself. He would reverse engineer this quadcopter’s radio protocol. His four-post series of exploits covers finding the right frequency for the radio, figuring out the protocol, and building his own remote for this cheap toy.

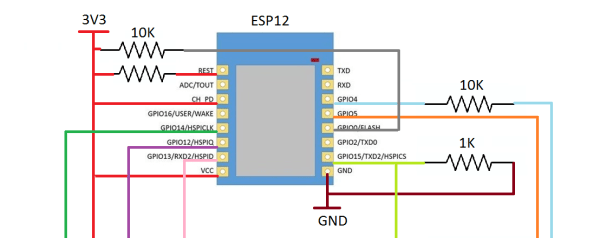

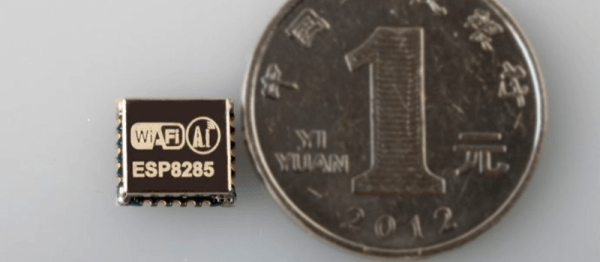

[Michael] was already familiar with the capabilities of these cheap toys after reading a Hackaday post, and the 75-page, four language manual cleared a few things up for him. The ‘Quadro-Copter’ operated on 2.4GHz, but did not give any further information. [Michael] didn’t know what channel the toy was receiving on, what data rate, or what the header for the transmission was. SDR would be a good tool for figuring this out, but thanks to Travis Goodspeed, there’s a really neat trick that will put a 2.4GHz nRF24L01+ radio into promiscuous mode, allowing [Michael] to read the transmissions between the transmitter and quadcopter. This code is available on [Michael]’s github.

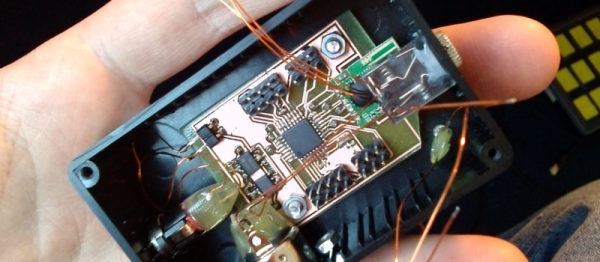

A needle in an electromagnetic haystack was found and [Michael] could listen in on the quadcopter commands. The next step was interpreting the ones and zeros, and with the help of a small breakout board and soldering directly to the SPI bus on the transmitter, [Michael] was able to do just that. By going through the nRF24 documentation, he was able to suss out the pairing protocol and read the stream of bytes that commanded the quadcopter.

What [Michael] was left with is a series of eight bytes sent in a continuous stream from the transmitter to the toy. These bytes contained the throttle, yaw, pitch, roll, and a ‘flip’ settings, along with three bytes of ‘counters’ that didn’t seem to do anything. With that info in hand, [Michael] took an Arduino Nano, an nRF04L01+ transceiver, and a Wii nunchuck to build his own transmitter. If you’re looking for a ‘how to reverse engineer’ guide, it generally doesn’t get better than this.

You can check out a video of [Michael] flying his Wiimoted quadcopter below.

Continue reading “Reverse Engineering Quadcopter Protocols” →