What’s going to keep a clock running for a century, unattended? Well, whatever’s running it will have to sip power, and it’s going to need a power source that will last a long time. [Jan Waclawek] is looking into solar power for daytime, and capacitors for nighttime, to keep his clock running for a hundred years.

This project carries on from [Jan]’s previous project which looked at what kind of power source could power the gadgets around his house for a century without needing intervention – ie., no batteries to replace, no winding etc. [Jan] whittled his choices down to a combination of solar power and polypropylene film capacitors. Once the power had been sorted, a clock was chosen in order to test the power supply. The power consumption for a clock will be low during the night – it would only need a RTC circuit keeping track of the time – so a few low-leakage capacitors can be used. When daylight returns or a light is switched on, the solar circuit would power the clock’s display.

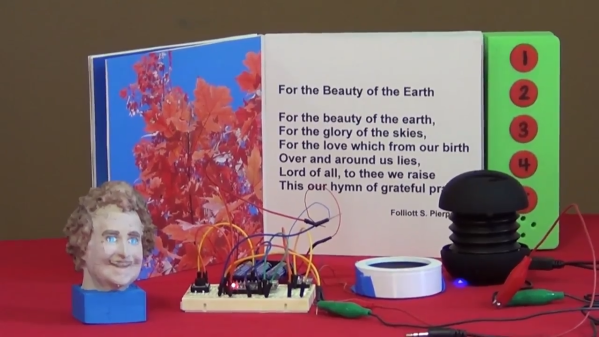

At the moment, [Jan] has a proof of concept circuit working, using the ultra-low-power microcontroller on a STM32L476 DISCOVERY board and a few 10 μF 0805 size capacitors, when fully charged by the solar panel, the clock’s display lasts for about two minutes.

Take a look at [Jan]’s project for more details, and check out his previous project where he narrowed down the components for a hundred-year power supply. [Jan]’s prototype can be seen in action after the break. Also take a look at this master clock that signals slave clocks and runs for a year on a single AA battery.