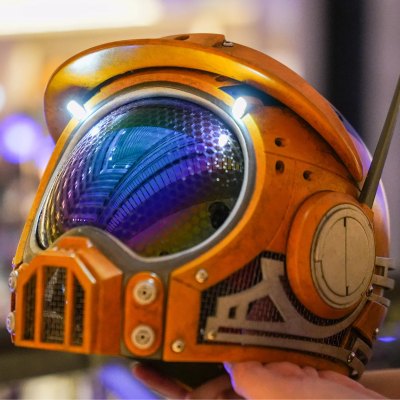

[GizmoThrill] shows off a design for an absolutely gorgeous, high-fidelity replica of the main character’s helmet from the video game Satisfactory. But the best part is the technique used to create the visor: just design around a cheap set of full-face “sunglasses” to completely avoid having to mold your own custom faceplate.

One of the most challenging parts of any custom helmet build is how to make a high-quality visor or faceplate. Most folks heat up a sheet of plastic and form it carefully around a mold, but [GizmoThrill] approached the problem from the other direction. After spotting a full-face sun visor online, they decided to design the helmet around the readily-accessible visor instead of the other way around.

The first thing to do with the visor is cover it with painter’s tape and 3D scan it. Once that’s done, the 3D model of the visor allows the rest of the helmet to be designed around it. In the case of the Satisfactory helmet, the design of the visor is a perfect match for the game’s helmet, but one could easily be designing their own custom headgear with this technique.

With the helmet 3D printed, [GizmoThrill] heads to the bandsaw to cut away any excess from the visor, and secure it in place. That’s all there is to it! Sure, you don’t have full control over the visor’s actual shape, but it sure beats the tons and tons of sanding involved otherwise.

There’s a video tour of the whole process that shows off a number of other design features we really like. For example, metal mesh in the cheek areas and in front of the mouth means a fan can circulate air easily, so the one doesn’t fog up the inside of the visor with one’s very first breath. The mesh itself is concealed with some greebles mounted on top. You can see all those details up close in the video, embedded just below.

The helmet design is thanks to [Punished Props] and we’ve seen their work before. This trick for turning affordable and somewhat gimmicky sunglasses into something truly time-saving is definitely worth keeping in mind.

Continue reading “Gimmick Sunglasses Become Easy Custom Helmet Visor”