Surfing is a fun and exciting sport but a lot of beginners can get discouraged with how little time is spent actually riding waves while learning. Not only are balance and wave selection critical skills that take time to learn, but a majority of time in the water is spent battling crashing waves to get out past the breakers. Many people have attempted to solve this problem through other means than willpower alone, and one of the latest attempts is [Andrew W] with a completely DIY surfboard with custom impeller jet drives.

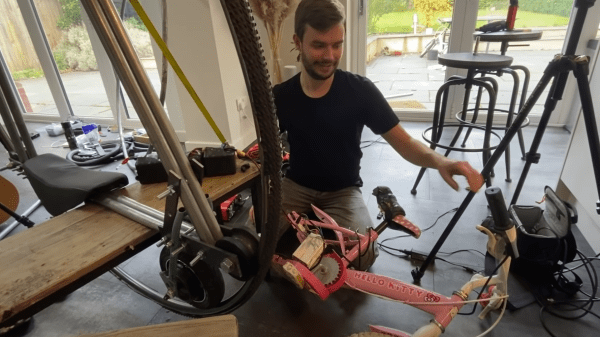

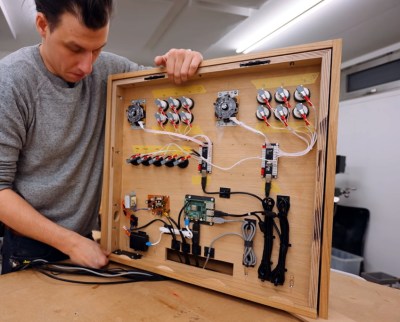

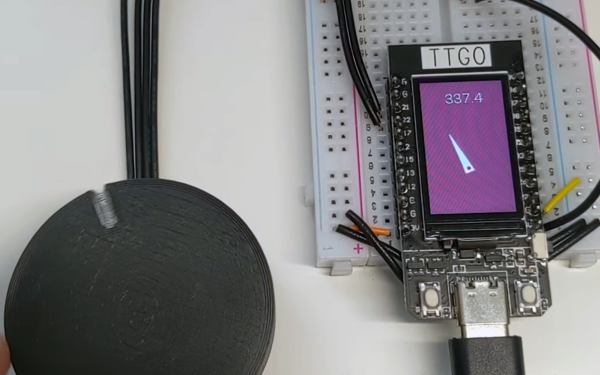

The surfboard is hand-made by [Andrew W] himself using a few blocks of styrofoam glued together and then cut into a generic surfboard shape. After the rough shaping is done, he cuts out a huge hole in the back of the board for the jet drive. This drive is almost completely built by [Andrew] as well including the impeller pumps themselves which he designed and 3D printed. The pair of impellers are driven by some beefy motors and a robust speed controller that connects wirelessly to a handheld waterproof throttle to hold while surfing. Once everything was secured in the motor box the surfboard was given a final shaping and then glassed. The final touch was an emergency disconnect attached to a leash so that if he falls off the board it doesn’t speed away without him.

The build is impressive not only for [Andrew]’s shaping skills but for his dedication to a custom jet drive for the surfboard. He spent over a year refining the build and actually encourages people not to do this as he thinks it took too much time and effort, but we’re going to have to disagree with him there. Even if you want to try to build something a lot simpler, builds like these look like a lot of fun once they’re finished. The build seems flawless and while he only tested it in a lake we’re excited to see if it holds up surfing real waves in an ocean.