Printing on fabric might be a familiar trick, but adding stretch into the equation gives our fabric prints the ability to reconstitute themselves back into 3D. That’s exactly what [Gabe] has accomplished; he’s developed a script that takes open 3d meshes and converts them to a hexagonal pattern that, when 3D-printed on a stretched fabric, lets them pop into 3D upon relaxing the fabric.

[Gabe’s] algorithm first runs an open 3D surface through the “Boundary-First Flattening Algorithm,” which gives [Gabe] a 2D mesh of triangles. Triangles are then mapped to hexagons based on size, which produces a landscape of 2D hexagons. Simply printing this hexagonal pattern onto prestretched fabric defines the shape of the object that will surface when the fabric is allowed to relax. As for how to wrap our heads around the mapping algorithm, as [Gabe] explains it, “The areas that experienced the most shrinkage in the flattening process should experience the least shrinkage when the fabric contracts after printing, and the regions that experienced little to no shrinkage in the flattening process should contract as much as possible in the fabric representation.”

If that seems tricky to visualize, just imagine taking a cheap halloween mask and trying to crush it flat onto a table. To smush it perfectly flat, some sections need to stretch while others need to shrink. Once flat though, we can simply keep stretching to remove all the sections that needed to shrink. At this point, if our material were extremely elastic, we could simply let go and watch our rubber mask jump back into 3D. That’s the secret behind [Gabe’s] hexagonal pattern. The size and spacing of these hexagons limit the degree to which local regions of the fabric are allowed to contract. In our rubber mask example, the sections that we stretched out the furthest have the most to travel, so they should contract as much as possible, while the sections that shrank in the initial flattening (although we kept stretching until they too needed to stretch) should shrink the least.

We’ve seen some classy fabric-printing tricks in the past. If you’re hungry for more 3D printing on fabric, have a look at [David Shorey’s] flexible fabric designs.

Thanks for the tip, [Amy]!

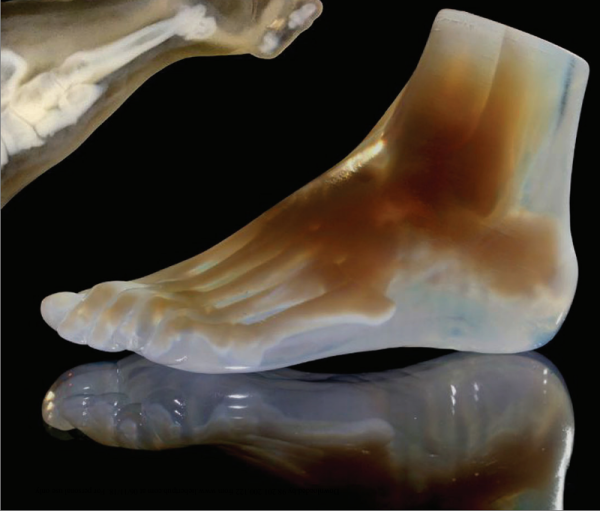

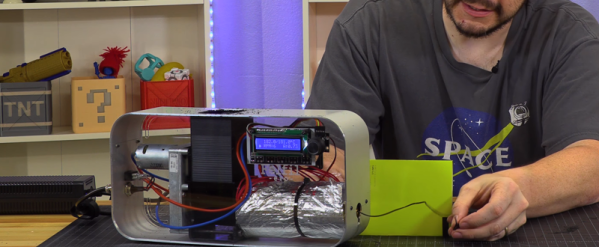

The Exchange is dominated, at least in terms of sheer numbers, by 3D models of proteins and other biochemical structures. But there are two sections that will appeal to the hacker in you: prosthetics and lab equipment. Indeed, we were sent there after finding a nice model of a tray-agitator that we wanted to use for PCB etching. We haven’t printed one yet, but check out this flexible micropositioner.

The Exchange is dominated, at least in terms of sheer numbers, by 3D models of proteins and other biochemical structures. But there are two sections that will appeal to the hacker in you: prosthetics and lab equipment. Indeed, we were sent there after finding a nice model of a tray-agitator that we wanted to use for PCB etching. We haven’t printed one yet, but check out this flexible micropositioner.