There are hundreds if not thousands of artifacts from the Apollo program scattered around the globe, some twisted wrecks at the bottom of the ocean, others lovingly preserved and sitting in museums or in the hands of private collectors. All of what’s left is pretty much pure unobtainium, so if you want something Apollo-like, you’re probably going to have to make it yourself.

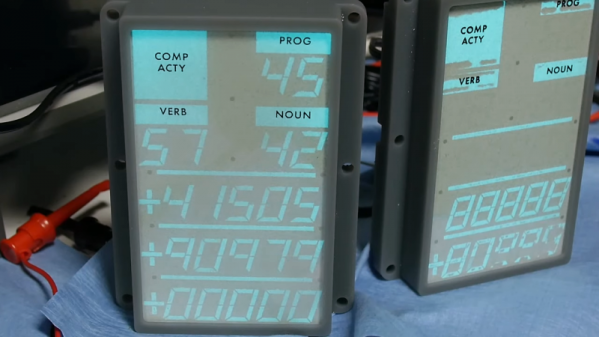

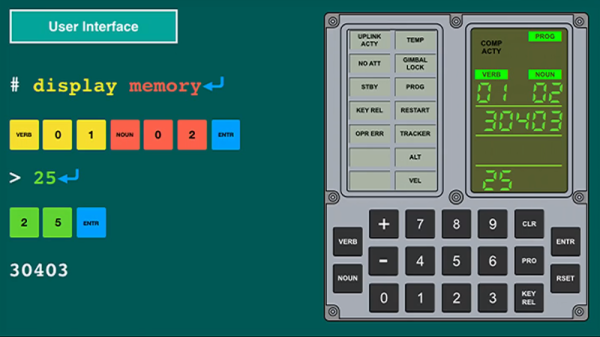

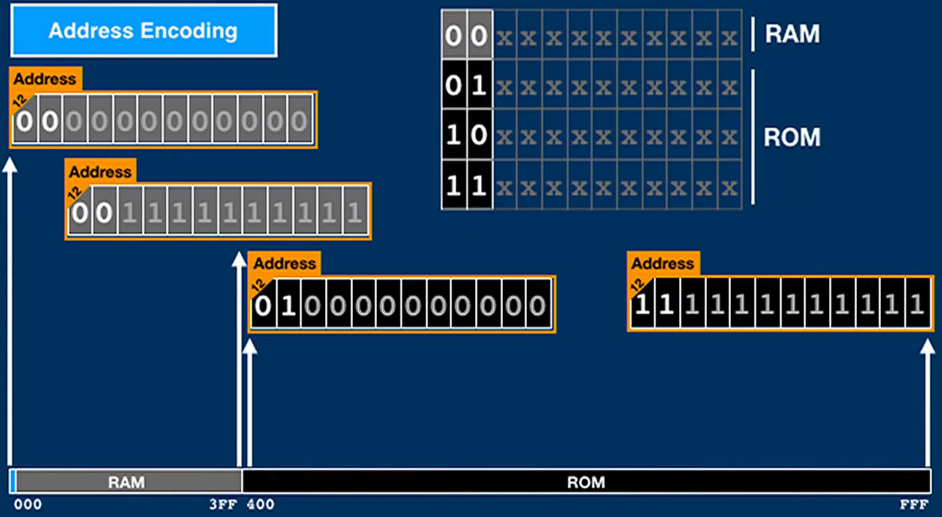

[Ben Krasnow] took up the challenge to make an electroluminescent Apollo-era DSKY display from scratch, with outstanding results. The DSKY, or “display and keyboard”, was the user interface for the Apollo Guidance Computer, the purpose-built digital navigation system that got a total of 24 men there and back again. [Ben] says it took a long time to recreate the display, and we can see why. He needed to master quite a few skills, including screen printing to get the glass-panel display working. The panel is a sandwich of phosphorescent paint, a dielectric, and conductive ink. The ink is silkscreened on the back to form the characters, all applied to indium tin oxide (ITO) conductive glass. A PCB with the same pattern of character segments lays behind that, driving each segment with 300 volts or so through a trio of HV507 high-voltage shift registers. It’s an impressive bit of engineering and gives off a decidedly not-homebrew vibe.

In the video below, [Ben] goes into detail about the trials he experienced on the way to this amazing endpoint, not least of which was frying chip after chip due to ineffective protection diodes in the shift registers. That’s an epic debugging story that’s worth the price of admission all by itself. It’s not the only DSKY in town, of course – [Fran Blanche] has been working on one for a while too – but there’s just something about that blue glow that we really like.

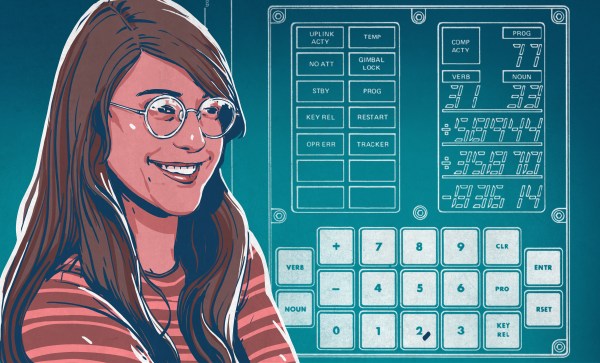

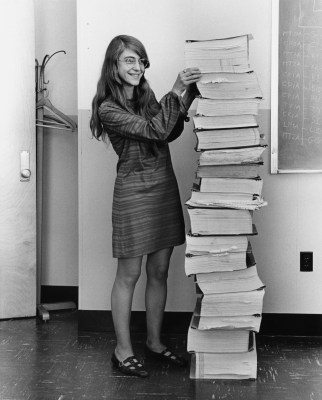

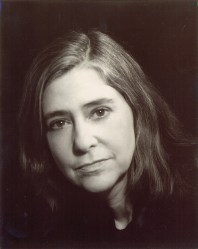

Hamilton soon moved on to the SAGE program, writing software which would monitor radar data for incoming Russian bombers. Her work on SAGE put Margaret in the perfect position to jump to the new Apollo navigation software team.

Hamilton soon moved on to the SAGE program, writing software which would monitor radar data for incoming Russian bombers. Her work on SAGE put Margaret in the perfect position to jump to the new Apollo navigation software team.

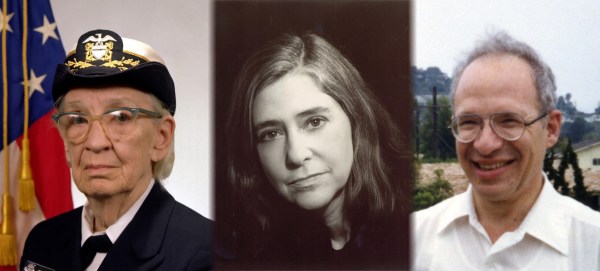

As Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming,

As Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming,  Physicist

Physicist