Here’s a design for a split-flap clock that doesn’t do it the usual way. Instead of the flaps showing numbers , Klapklok has a bit more in common with flip-dot displays.

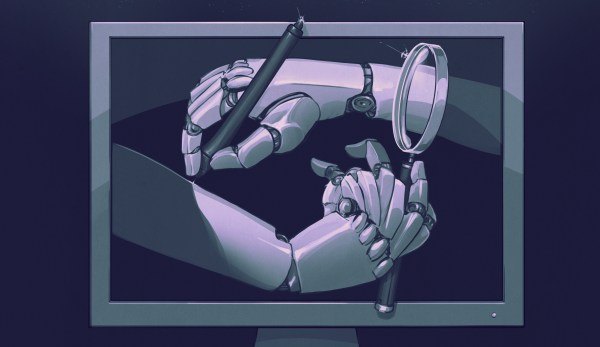

It’s an art piece that uses custom-made split-flaps which flutter away to update the display as time passes. An array of vertically-mounted flaps creates a sort of low-res display, emulating an analog clock. These are no ordinary actuators, either. The visual contrast and cleanliness of the mechanism is fantastic, and the sound they make is less of a chatter and more of a whisper.

The sound the flaps create and the sight of the high-contrast flaps in motion are intended to be a relaxing and calming way to connect with the concept of time passing. There’s some interactivity built in as well, as the Klapklok also allows one to simply draw on it wirelessly with via a mobile phone.

Klapklok has a total of 69 elements which are all handmade. We imagine there was really no other way to get exactly what the designer had in mind; something many of us can relate to.

Split-flap mechanisms are wonderful for a number of reasons, and if you’re considering making your own be sure to check out this easy and modular DIY reference design before you go about re-inventing the wheel. On the other hand, if you do wish to get clever about actuators maybe check out this flexible PCB that is also its own actuator.

Continue reading “Split-Flap Clock Flutters Its Way To Displaying Time Without Numbers”