A subset of hackers have RFID implants, but there is a limited catalog. When [Miana] looked for a device that would open a secure door at her work, she did not find the implant she needed, even though the lock was susceptible to cloned-chip attacks. Since no one made the implant, she set herself to the task. [Miana] is no stranger to implants, with 26 at the time of her talk at DEFCON31, including a couple of custom glowing ones, but this was her first venture into electronic implants. Or electronics at all. The full video after the break describes the important terms.

The PCB antenna in an RFID circuit must be accurately tuned, which is this project’s crux. Simulators exist to design and test virtual antennas, but they are priced for corporations, not individuals. Even with simulators, you have to know the specifics of your chip, and [Miana] could not buy the bare chips or find a datasheet. She bought a pack of iCLASS cards from the manufacturer and dissolved the PVC with acetone to measure the chip’s capacitance. Later, she found the datasheet and confirmed her readings. There are calculators in lieu of a simulator, so there was enough information to design a PCB and place an order.

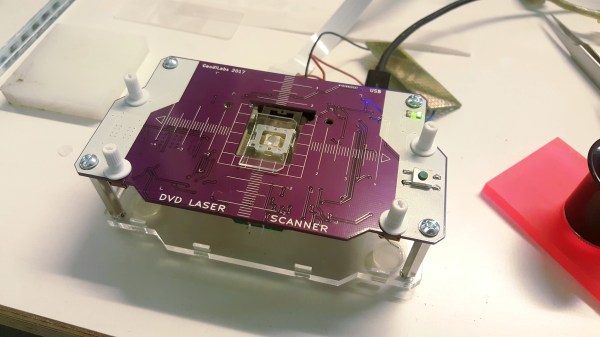

The first batch of units can only trigger the base station from one position. To make the second version, [Miana] bought a Vector Network Analyzer to see which frequency the chip and antenna resonated. The solution to making adjustments after printing is to add a capacitor to the circuit, and its size will tune the system. The updated design works so a populated board is coated and implanted, and you can see an animated loop of [Miana] opening the lock with her bare hand.

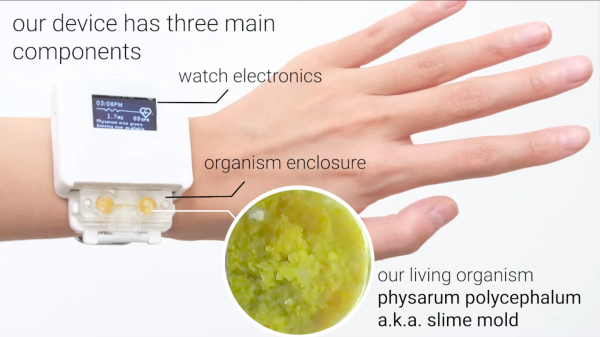

Biohacking can be anything from improving how we read our heart rate to implanting a Raspberry Pi.

Continue reading “Bespoke Implants Are Real—if You Put In The Time”