It’s probably clear to a Hackaday reader that we live in a golden era for hobbyist tool accessibility. Cheap single board computers can be bought at any neighborhood RadioShack or Maplin. 3D printers sell fully assembled and ready to run for less than $200. Even the humble CNC mill has come down the price curve, though as you might expect at the low end things can get pretty rough. Like a cheap 3D printer, a cheap mill tends to be missing some basic features you’d expect any reasonable machine to have. If you get your hands on one of these little wonders, [Shahada Abubakar] has a pair of great blog posts on the basic set of upgrades you’ll probably want to perform right out of the box.

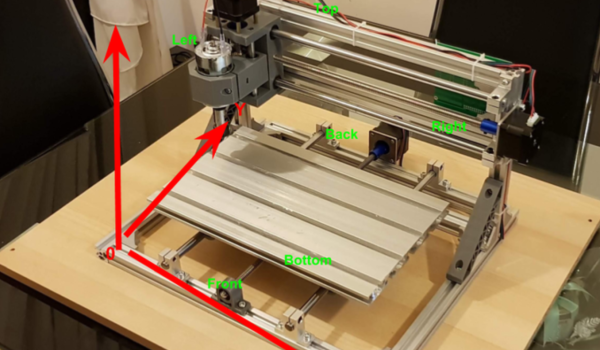

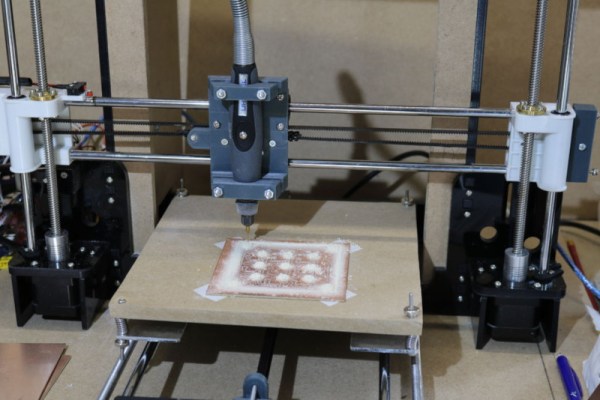

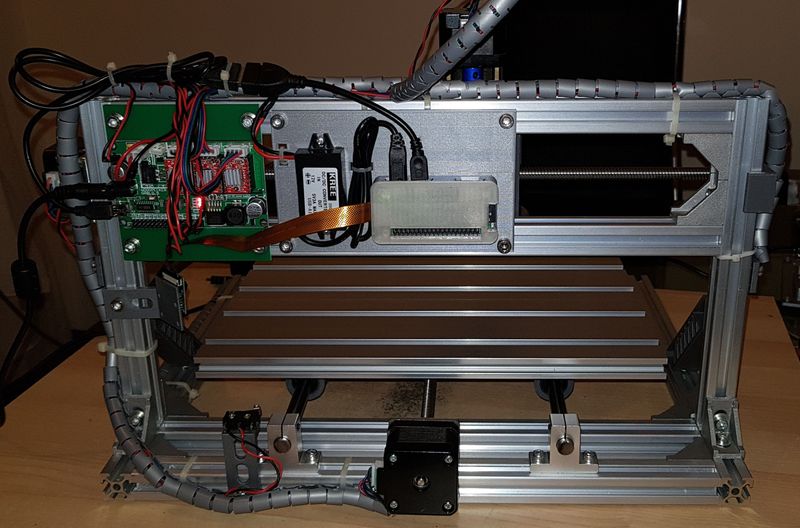

Which cheap CNC mills are we talking about? They go by a few names. Last year our own [Kristina Panos] put together a review of a shockingly inexpensive “1610” type sold by Linksprite (go take a read if you’re already considering a purchase!). The “1610” class, so named for it’s 16 cm x 10 cm bed size, is pretty common under a wide variety of manufacturer names. You can find them in this size made of 8020 like [Kristina] did or as “upgraded” versions cut from 1/4″ mystery plastic (often referred to in the listings as Bakelite, but your guess is as good as ours as to the true material). 1610 is the smallest size but basically the same machine exists as an 1810, 2418, or 3018. Each has a 775 size spindle and a single PCBA that handles stepper drive and runs grbl.

Which cheap CNC mills are we talking about? They go by a few names. Last year our own [Kristina Panos] put together a review of a shockingly inexpensive “1610” type sold by Linksprite (go take a read if you’re already considering a purchase!). The “1610” class, so named for it’s 16 cm x 10 cm bed size, is pretty common under a wide variety of manufacturer names. You can find them in this size made of 8020 like [Kristina] did or as “upgraded” versions cut from 1/4″ mystery plastic (often referred to in the listings as Bakelite, but your guess is as good as ours as to the true material). 1610 is the smallest size but basically the same machine exists as an 1810, 2418, or 3018. Each has a 775 size spindle and a single PCBA that handles stepper drive and runs grbl.

So what’s the problem? Well for one none of these machines have limit switches, though the controllers support them. [Shahada]’s guide has handy instructions for what kind to buy, how to wire them, and where they can be attached. Plus an overview of the G-code instructions to send the controller in order to home and configure everything properly. The controllers also like to be driven continuously over serial (though some sellers seem to offer a separate board to drive them). This is fine if you have a computer handy, but like a 3D printer it can be nice to bolt a Pi Zero or similar onto the unit and control it over the network. [Shahada]’s second post has a link to a mounting plate you can print for exactly that setup, as well as some suggestions for configuring CNC.js to drive everything.

Do you have one of these machines? Done any upgrades? Tell us in the comments! We’re always looking for ways to upgrade our home shop.