We’re probably all familiar with the Hall Effect, at least to the extent that it can be used to make solid-state sensors for magnetic fields. It’s a cool bit of applied physics, but there are other ways to sense magnetic fields, including leveraging the weird world of quantum physics with this diamond, laser, and microwave open-source sensor.

Having never heard of quantum sensors before, we took the plunge and read up on the topic using some of the material provided by [Mark C] and his colleagues at Quantum Village. The gist of it seems to be that certain lab-grown diamonds can be manufactured with impurities such as nitrogen, which disrupt the normally very orderly lattice of carbon atoms and create a “nitrogen vacancy,” small pockets within the diamond with extra electrons. Shining a green laser on N-V diamonds can stimulate those electrons to jump up to higher energy states, releasing red light when they return to the ground state. Turning this into a sensor involves sweeping the N-V diamond with microwave energy in the presence of a magnetic field, which modifies which spin states of the electrons and hence how much red light is emitted.

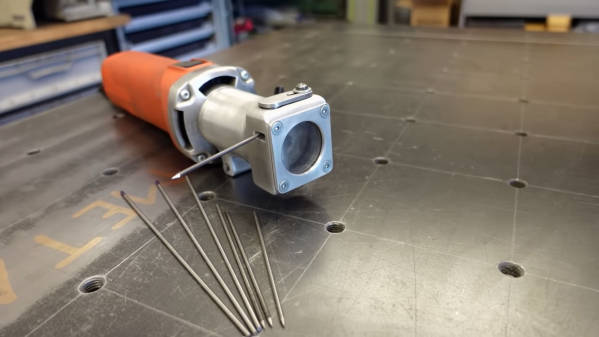

Building a practical version of this quantum sensor isn’t as difficult as it sounds. The trickiest part seems to be building the diamond assembly, which has the N-V diamond — about the size of a grain of sand and actually not that expensive — potted in clear epoxy along with a loop of copper wire for the microwave antenna, a photodiode, and a small fleck of red filter material. The electronics primarily consist of an ADF4531 phase-locked loop RF signal generator and a 40-dB RF amplifier to generate the microwave signals, a green laser diode module, and an ESP32 dev board.

All the design files and firmware have been open-sourced, and everything about the build seems quite approachable. The write-up emphasizes Quantum Village’s desire to make this quantum technology’s “Apple II moment,” which we heartily endorse. We’ve seen N-V sensors detailed before, but this project might make it easier to play with quantum physics at home.