When you think of a shooting gallery, you might envision a line of tin cans set up along a split-rail fence, or a few rows of ducks or bottles lined up at a carnival. But what do these have in common? You, standing in one spot, and shooting in the same general direction. You’re exposed! If those targets could shoot back, you’d be dead within seconds. Wouldn’t it be more fun if the targets were all around you in 360°? We think so, too.

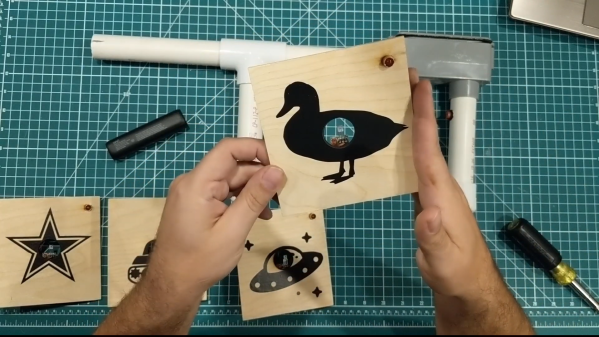

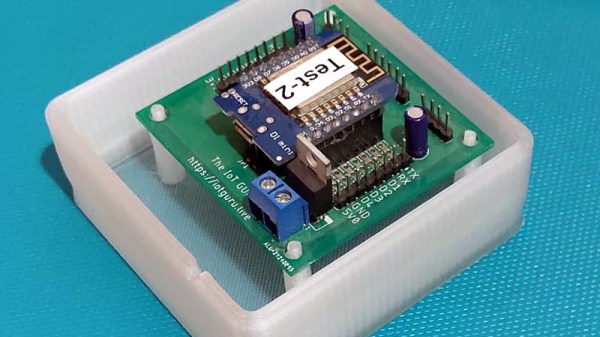

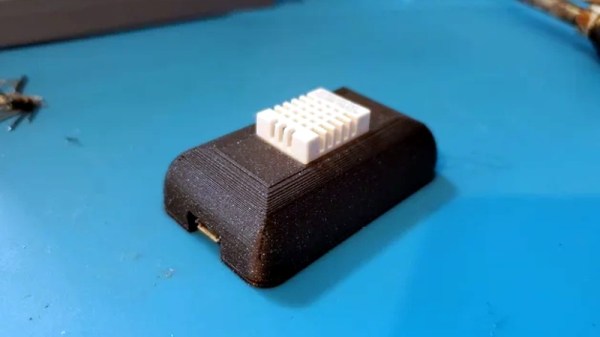

So how could you possibly set up a shooting gallery this way? [Another Maker] already solved that problem for you with ESP32s and Node-RED (YouTube). Each target has an ESP32, a laser sensor, and an LED that lights up when the target is ready, and turns off once it’s been hit. They all make an enticing ‘shoot me’ sound that goes with their graphics, and a second mp3 plays upon direct hit.

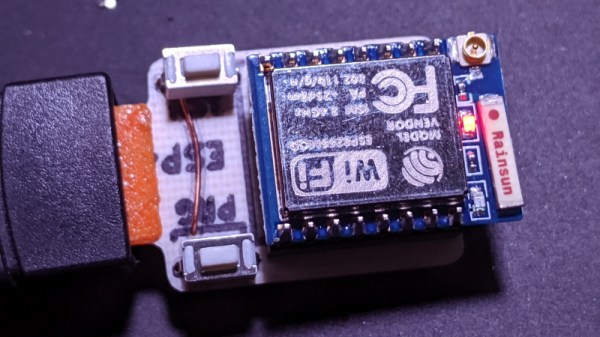

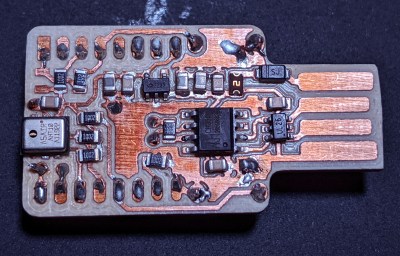

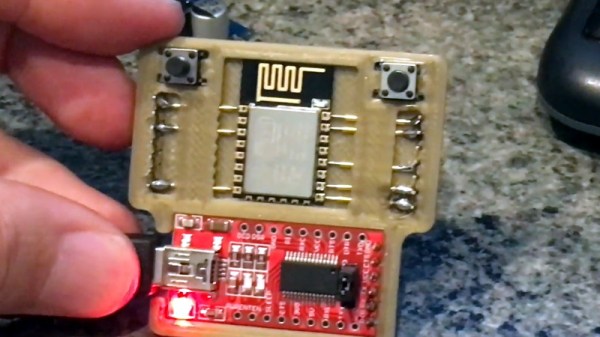

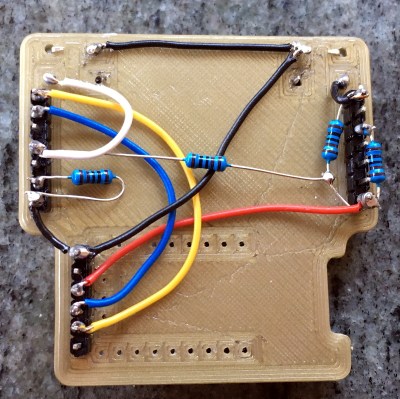

The PVC gun houses an ESP8266, a laser module at the end of the barrel, and runs on a cylindrical USB battery slipped down in the secondary grip. [Another Maker] can spread the targets out far and wide, as long as they all stay in range of the localized WiFi access point.

The best part is that the Node-RED system is target-agnostic — it doesn’t care how many you have or how they’re made, and it can juggle up to 250 of them. Because of the way the target objects are programmed, it would be quite easy to add actuators that make them drop down or fall backward when hit. You could also implement [Another Maker]’s fantastic suggestion of hitting arcade buttons with NERF darts instead. Charge those lasers and fire at the break button to see the demo and walk-through video.

If you plan to knock the targets down or over in your implementation, you’ll want an easy way to reset them. Here’s a scrap-built shooting gallery that uses a windshield wiper motor to set ’em back up.