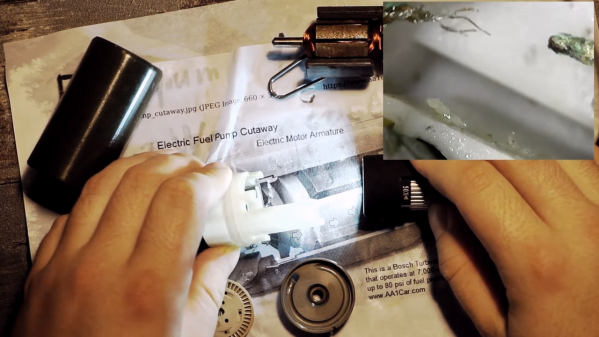

[Will Stelter], a promising young blacksmith working out of Montana, had a terrific idea for a unique composite material for finishing off a knife build. This build is a collaboration between multiple blacksmiths, and as the youngster of the group, [Will] really wanted to pull out the stops and finally make a material he’d been contemplating for years to impress the elders. He knows that if you try to forge wrought iron at too low a temperature, it develops cracks and splits. Could you do this on purpose, and then fill these cracks with bronze? It would be quite the stunning material, with the bright bronze veins running through the dark iron. He had to try.

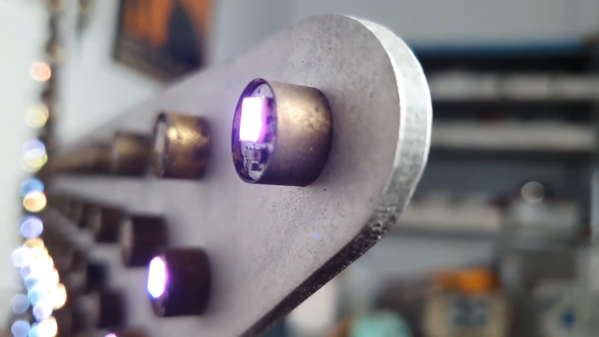

Unfortunately, our young experimenter ran into some problems that didn’t have enough time to overcome. First, getting the bronze to flow and fill the voids of the iron was a challenge, particularly when heating with a torch. Throwing the whole experiment into a forge resulted in the bronze leaking through the enclosure. The most promising attempt was a beefed-up box, set in an oven for about 20 minutes, with the temperature high enough to liquefy the bronze. It was looking great, until he cut into it and found too many air pockets for a workable billet.

The attempt was a failure, but we’re delighted that [Will] went ahead and put the video out there anyway. And if you know how to make this work, go drop a comment on his channel, and we’ll all look forward to a part two, where he finally nails the technique.

Continue reading “Fail Of The Week: Bronze-Brazed Wrought Iron”