It’s a well-known fact that anti-ferromagnetic materials are called that way because they cannot be magnetized, not even in the presence of a very strong external magnetic field. The randomized spin state is also linked with any vibrations (phonons) of the material, ensuring that there’s a very strong resistance to perturbations. Even so, it might be possible to at least briefly magnetize small areas through the use of THz-range lasers, as they disrupt the phonon-spin balance sufficiently to cause a number of atoms to ‘flip’, resulting in a localized magnetic structure.

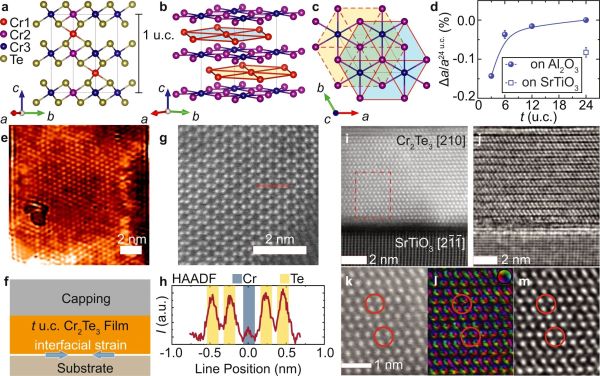

The research by [Baatyr Ilyas] and colleagues was published in Nature, describing the way the 4.8 THz pulses managed to achieve this feat in FePS3 anti-ferromagnetic material. The change in spin was verified afterwards using differently polarized laser pulses, confirming that the local structures remained intact for at least 2.5 milliseconds, confirming the concept of using an external pulse to induce phonon excitation. Additional details can be found in the supplemental information PDF for the (sadly paywalled with no ArXiv version) paper.

As promising as this sounds, the FePS3 sample had to be cooled to 118K and kept in a vacuum chamber. The brief magnetization also doesn’t offer any immediate applications, but as a proof of concept it succinctly demonstrates the possibility of using anti-ferromagnetic materials for magnetic storage. Major benefit if such storage can be made more permanent is that it might be more stable and less susceptible to outside influences than traditional magnetic storage. Whether it can be brought out of the PoC stage into at least a viable prototype remains to be seen.