During World War II, shipboard life in the United States Navy was a gamble. No matter which theater of operations you found yourself in, the enemy was all around on land, sea, and air, ready to deliver a fatal blow and send your ship to the bottom. Fast forward a couple of decades and Navy life was just as hazardous but in a different way, as this Navy training film on the shipboard hazards of low-voltage electricity makes amply clear.

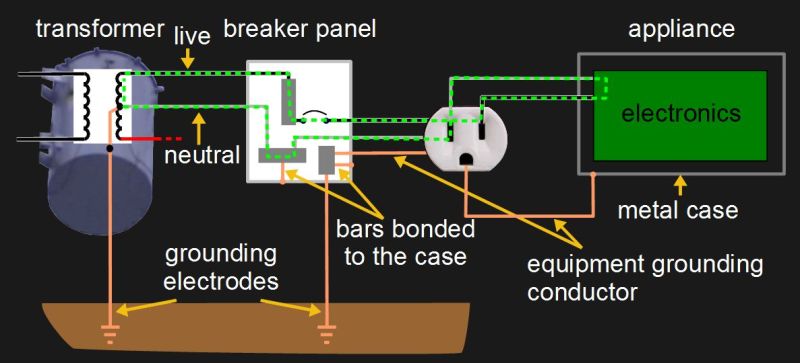

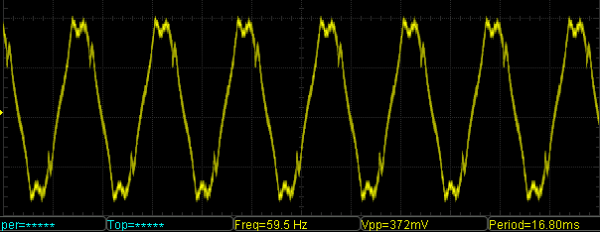

With the suitably scary title “115 Volts: A Deadly Shipmate,” the 1960 film details the many and various ways sailors could meet an untimely end, most of which seemed to circle back to attempts to make shipboard life a little more tolerable. The film centers not on the risks of a ship’s high-voltage installations, but rather the more familiar AC sockets used for appliances and lighting around most ships. The “familiarity breeds contempt” argument rings a touch hollow; given that most of these sailors appear to be in their 20s and 30s and rural electrification in the US was still only partially complete through the 1970s, chances are good that at least some of these sailors came from farms that still used kerosene lamps. But the point stands that plugging an unauthorized appliance into an outlet on a metal ship in a saltwater environment is a recipe for being the subject of a telegram back home.

The film shows just how dangerous mains voltage can be through a series of vignettes, many of which seem contrived but which were probably all too real to sailors in 1960. Many of the scenarios are service-specific, but a few bear keeping in mind around the house. Of particular note is drilling through a bulkhead and into a conduit; we’ve come perilously close to meeting the same end as the hapless Electrician’s Mate in the film doing much the same thing at home. As for up-cycling a discarded electric fan, all we can say is even brand new, that thing looks remarkably deadly.

The fact that they kept killing the same fellow over and over for each of these demonstrations doesn’t detract much from the central message: follow orders and you’ll probably stay alive. In an environment like that, it’s probably not bad advice.