The theme of this year’s Hackaday Prize is. ‘build something that matters.’ A noble goal, but there’s also a second prize – the Best Product prize – that is giving $100k to one lucky team who can appeal to people with open jaws and wallets. It’s a fabulous prize that also includes a six month residency at the Hackaday Design Lab, but right now there aren’t many contenders for this part of The Hackaday Prize.

[drewrisinger]’s DrDAC USB Audio DAC is one of those project that’s in the running for the Best Product prize. He’s solving the problem of terrible low-quality built-in soundcards that seem to be everywhere. Yes, it’s a simple idea, but the execution is great.

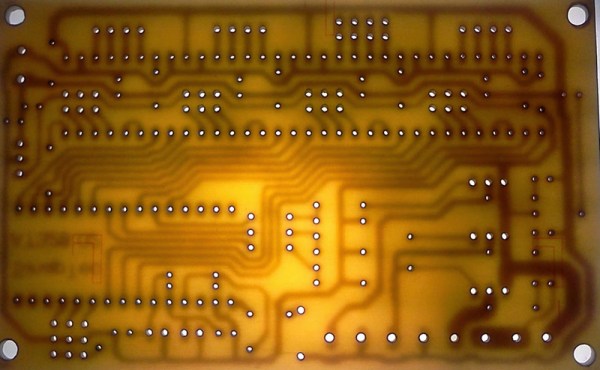

The electronics for DrDAC are pretty much what you would expect for a DIY audio sound card; A PCM2706 takes USB audio and sends it out over I2S. A PCM1794 converts the I2S to analog audio, and an OPA2836 amplifies it and sends everything out through a 1/8″ jack or a pair of RCA plugs.

[drewrisinger] started DrDAC as a school project, and after receiving the PCBs, he noticed a problem. MultiSim’s footprint for a TQFP-32 package was too small, meaning the IC simply wouldn’t fit on the board. It was too late in the semester to order a new board, meaning some sort of rework needed to happen. [drew] fixed this problem by soldering jumper wires between the pads to the leads of the chip. Yes, it looks crazy, but apparently it works. You can check out a video of that whole process below.