Sometimes the best part of building something is getting to rebuild it again a little farther down the line. Don’t tell anyone, but sometimes when we start a project we don’t even know where the end is going to be. It’s a starting point, not an end destination. Who wants to do something once when you could do it twice? Maybe even three times for good measure?

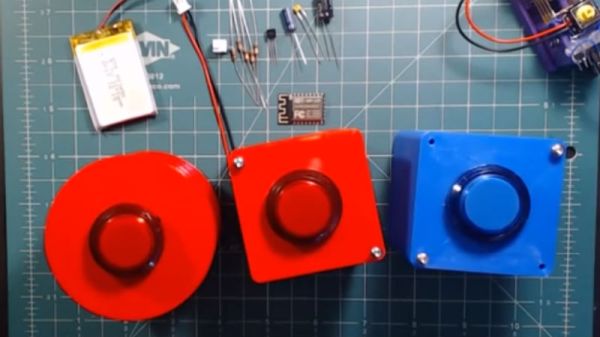

That’s what happened when [Ryan] decided to build a wireless “party button” for his kids. Tied into his Home Assistant automation system, a smack of the button plays music throughout the house and starts changing the colors on his Philips Hue lights. His initial version worked well enough, but in the video after the break, he walks through the evolution of this one-off gadget into a general purpose IoT interface he can use for other projects.

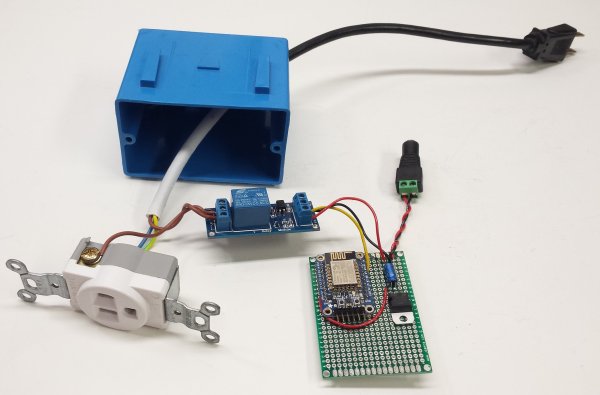

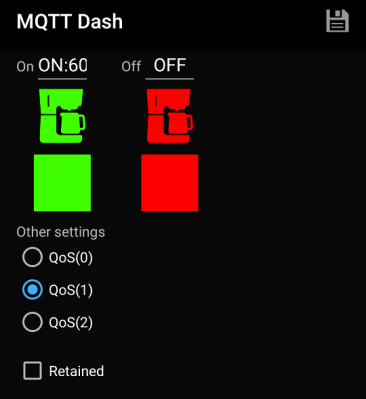

The general idea is pretty simple, the big physical button on the top of the device resets the internal ESP8266, which is programmed to connect to his home WiFi and send a signal to his MQTT server. In the earlier versions of the button there was quite a bit of support electronics to handle converting the momentary action of the button to a “hard” power control for the ESP8266. But as the design progressed, [Ryan] realized he could put the ESP8266 to deep sleep after it sends the signal, and just use the switch to trigger a reset on the chip.

Additional improvements in the newer version of the button include switching from alkaline AA batteries to a rechargeable lithium-ion pack, and even switching over to a bare ESP8266 rather than the NodeMCU development board he was using for the first iteration.

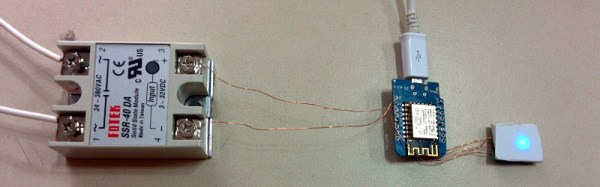

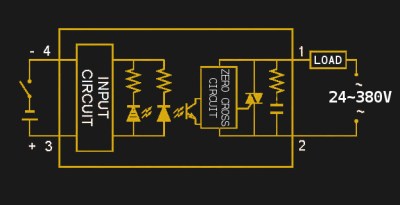

For another take on MQTT home automation with the ESP8266, check out this automatic garage door control system. If the idea of triggering a party at the push of a button has your imagination going, we’ve seen some elaborate versions of that idea as well.