The fortunate among us may very well have a bit of time off from work coming up, and while most of that time will likely be filled with family obligations and festivities, there’s probably going to be some downtime. And if you should happen to find yourself with a half hour free, you might want to check out the Clickspring Byzantine Calendar-Sundial mega edit. And we’ll gladly accept your gratitude in advance.

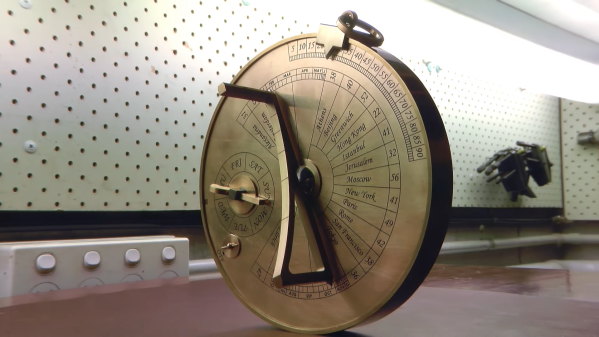

Fans of machining videos will no doubt already be familiar with Clickspring, aka [Chris], the amateur horologist who, through a combination of amazing craftsmanship and top-notch production values, managed to make clockmaking a spectator sport. We first caught the Clickspring bug with his open-frame clock build, which ended up as a legitimate work of art. [Chris] then undertook two builds at once: a reproduction of the famous Antikythera mechanism, and the calendar-sundial seen in the video below.

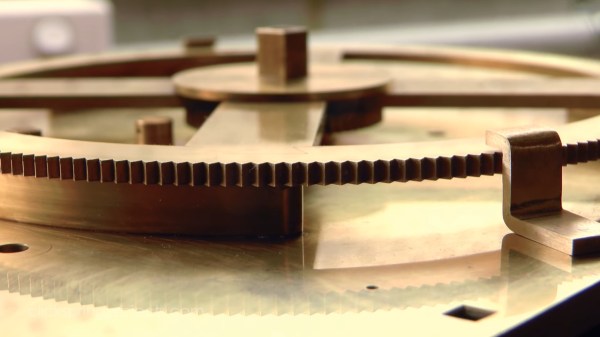

The cut condenses 1,000 hours of machining, turning, casting, heat-treating, and even hand-engraving of brass and steel into an incredibly relaxing video. There’s no narration, no exposition — nothing but the sounds of metal being shaped into dozens of parts that eventually fit perfectly together into an instrument worthy of a prince of Byzantium. This video really whets our appetite for more Antikythera build details, but we understand that [Chris] has been busy lately, so we’ll be patient.

Continue reading “For Your Holiday Relaxation: The Clickspring Sundial Build Megacut”