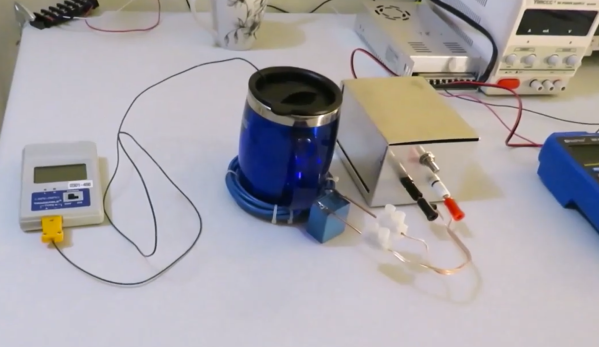

Like many hackers, [Matthias Wandel] has a penchant for measuring the world around him, and quantifying the goings-on in his home is a bit of a hobby. And so when it came time to sense the current flowing in the wires of his house, he did what any of us would do: he built his own current sensing system.

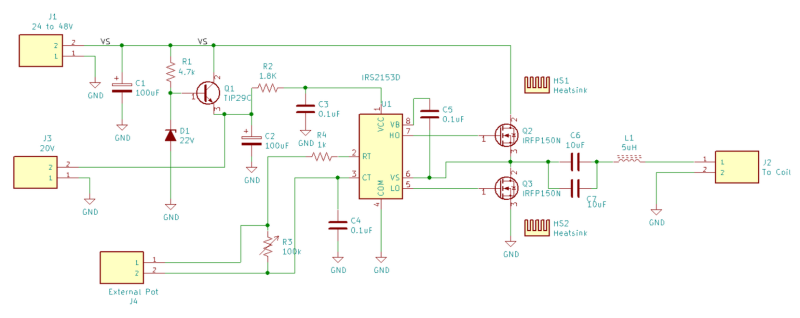

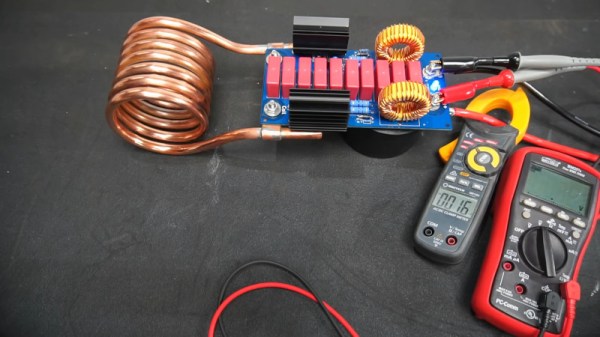

What’s that you say? Any sane hacker would buy something like a Kill-a-Watt meter, or even perhaps use commercially available current transformers? Perhaps, but then one wouldn’t exactly be hacking, would one? [Matthias] opted to roll his own sensors for quite practical reasons: commercial meters don’t quite have the response time to catch the start-up spikes he was interested in seeing, and clamp-on current transformers require splitting the jacket on the nonmetallic cabling used in most residential wiring — doing so tends to run afoul of building codes. So his sensors were simply coils of wire shaped to fit the outside of the NM cable, with a bit of filtering to provide a cleaner signal in the high-noise environment of a lot of switch-mode power supplies.

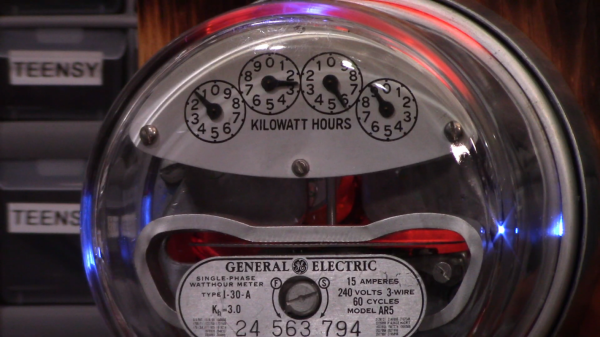

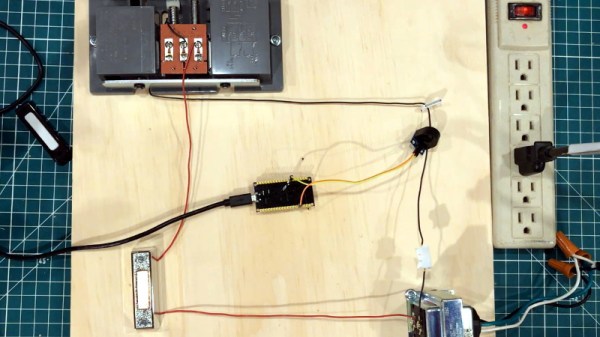

Fed through an ADC board into a Raspberry Pi, [Matthias]’ sensor system did a surprisingly good job of catching the start-up surge of some tools around the shop. That led to the entertaining “Circuit Breaker Challenge” part of the video below, wherein we learn just what it really takes to pop the breaker on a 15-Amp branch circuit. Spoiler alert: it’s a lot.

Speaking of staying safe with mains current, we’ve covered a little bit about how circuit protection works before. If you need a deeper dive into circuit breakers, we’ve got that too.