IoT-ifying old stuff is cool. Or even new, offline stuff. It seems to be a trend. And it’s sexy. Yes, it is. Why are people doing this, you may ask: we say why not? Why shouldn’t a toaster be on the IoT? Or a drill press? Or a radio? Yes, a radio.

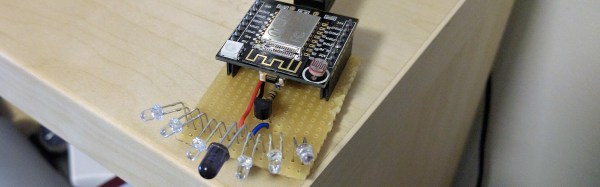

[Dr. Wummi] just added another device to the IoT, the Internet of Thongs as he calls it. It’s a Philips MCM205 Micro Sound System radio. He wanted to automate his radio but his original idea of building a setup with an infrared LED to remotely control it failed. He blamed it to “some funky IR voodoo”. So he decided to go for an ESP8266 based solution with a NodeMCU. ESP8266 IR remotes have been known to work before but maybe those were just not voodoo grade.

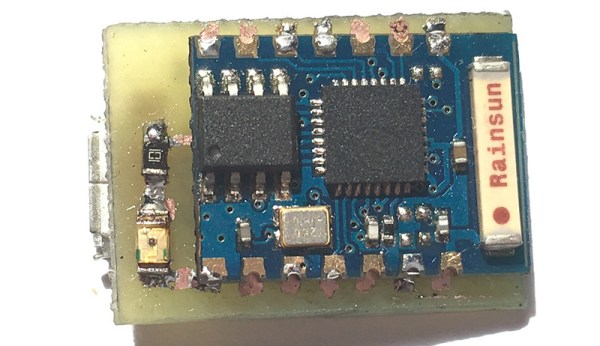

After opening the radio up, he quickly found that the actual AM/FM Radio was a separate module. The manufacturer was kind enough to leave the pins nicely labelled on the mainboard. Pins labelled SCL/SDA hinted that AM/FM module spoke I²C. He tapped in the protocol via Bus Pirate and it was clear that the radio had an EEPROM somewhere on the main PCB. A search revealed a 24C02 IC in the board, which is a 2K I²C EEPROM. So far so good but there were other functionalities left to control, like volume or CD playing. For that, he planned to tap into the front push button knob. The push button had different resistors and were wired in series so they generated different voltages at the main board radio ADC Pins. He tried to PWM with the NodeMCU to simulate this but it just didn’t work.

Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and

Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and