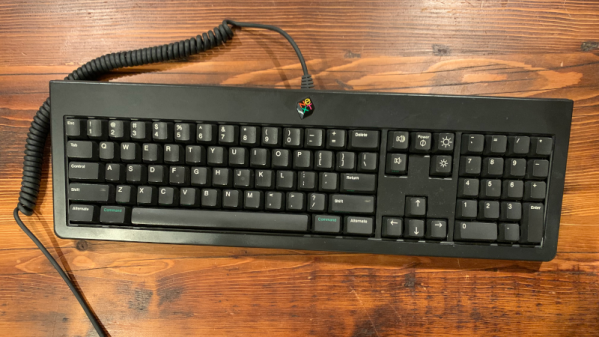

[10p6] wondered what it would be like if Atari had used a standardized keyboard across its 16-bit and 32-bit computer lines in 1985. Imagination is fun, but building things is even better, and thus they set out to create such a thing. Enter the Universal Atari Keyboard Case.

The case design is flexible, and can accept a keyboard from models including the Atari ST and Falcon. The keyboard can then be used with an Atari Mega, TT, or desktop-style Atari computers without mods. It also brings modern peripherals to bear on these old Atari platforms, enabling the use of modern USB mice while also using the two onboard joystick ports. Power and floppy LEDs are present, but subtly hidden beneath the case, only becoming visible when illuminated. It also includes 5-watt stereo speakers for getting the best out of the Atari’s sound hardware.

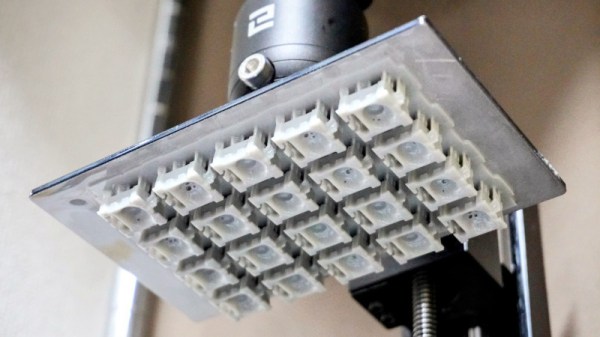

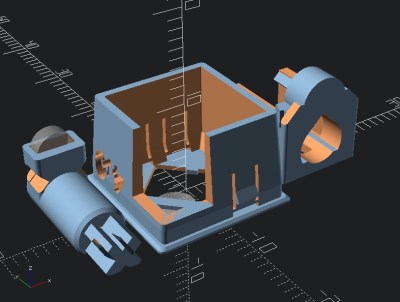

The final part, a full 473mm long, was 3D printed in resin for a high-quality surface finish. The results are so good it almost looks like a genuine factory keyboard.

If you’re regularly playing with your vintage Atari machines and you want a great keyboard to use with them, this could be the design for you. [10p6] has promised to soon upload the design files to Thingiverse for those eager to replicate the work.

We’ve also seen retro Atari keyboard converted to work with modern machines. Video after the break. Continue reading “Introducing The Universal Atari Keyboard Case”