Greetings fellow nerds. The Internet’s favorite artificial baritone chemist has a problem. His hotplates burn up too fast. He needs your help to fix this problem.

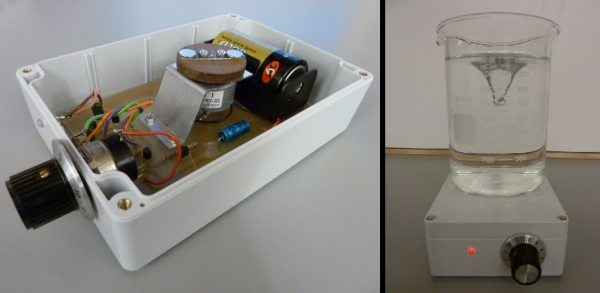

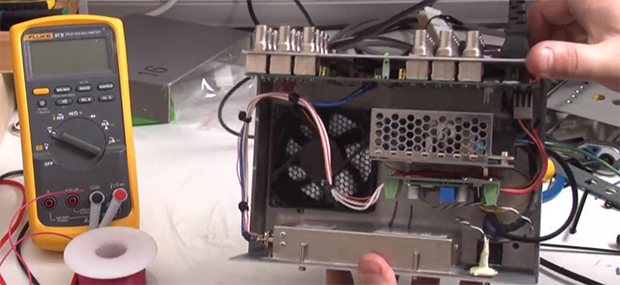

[NurdRage] is famous around these parts for his very in-depth explorations of chemistry including the best ways to etch a PCB, building a thermometer probe with no instructions, and chemical synthesis that shouldn’t be performed by anyone without years of experience in a lab. Over the past few years, he’s had a problem: hotplates suck. The heating element is usually poorly constructed, and right now he has two broken hotplates on his bench. These things aren’t cheap, either: a bare-bones hotplate with a magnetic stirrer runs about $600.

Now, [NurdRage] is asking for help. He’s contacted a few manufacturers in China to get a hundred or so of these hotplate heating elements made. Right now, the cost for a mica and metal foil hotplate is about $30 / piece, with a minimum order quantity of 100. That’s $3,000 that could be better spent on something a bit more interesting than a heating element, and this is where you come in: how do you build the heating element for a hotplate, and do it cheaply?

If you buy a hotplate from the usual lab equipment supplier, you’ll get a few pieces of mica and a thin trace of metal foil. Eventually, the metal foil will oxidize, and the entire hotplate will stop working. Repairs can be done with copper tape, but by the time that repair is needed, the heating element is already on its way out.

The requirements for this heating element include a maximum temperature of around 350 ºC. That’s a fair bit hotter than any PCB-based heat bed from a 3D printer gets, so consider that line of reasoning a dead end. This temperature is also above what most resins, thermoplastics, and composites can handle, which is why these hotplates use mica as an insulator.

Right now, [NurdRage] will probably end up spending $3,000 for a group buy of these heating elements. That’s really not that bad – for the price of five hotplates, he’ll have enough heating elements to last through the rest of his YouTube career. There must be a better way, though, so if you have an idea of how to make a high-temperature heating element the DIY way, leave a note in the comments.