It sounds like an overly complicated method a supervillain would use to slowly and painfully eliminate enemies — a chamber with variable oxygen concentration. This automated environmental chamber isn’t for torturing suave MI6 agents, though; rather, it enables cancer research more-or-less on the cheap.

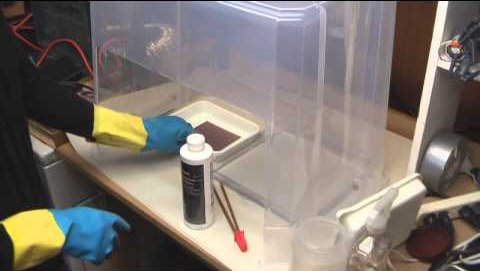

Tasked with building something to let his lab simulate the variable oxygen microenvironments found in some kinds of tumors, [RyanM415] first chose a standard lab incubator as a chamber to mix room air with bottled nitrogen. With a requirement to quickly vary the oxygen concentration from the normal 21% down to zero, he found that the large incubator took far too long to equilibrate, and so he switched to a small acrylic box. Equipped with a mixing fan, the smaller chamber quickly adjusts to setpoints, with an oxygen sensor providing feedback and controlling the gas valves via a pair of Arduinos. It’s quite a contraption, with floating ball flowmeters and stepper-actuated variable gas valves, but the results are impressive. If it weren’t for the $2000 oxygen sensor, [RyanM145] would have brought the whole project in for $500, but at least the lab can use the sensor elsewhere.

Modern biology and chemistry labs are target-rich environments for hacked instrumentation. From DIY incubators to cheap electrophoresis rigs, we’ve got you covered.

Continue reading “Automated Chamber Passes Just The Right Gas”