For a long while, digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras were the king of the castle for professional and amateur photography. They brought large sensors, interchangeable lenses, and professional-level viewfinders to the digital world at approachable prices, and then cemented their lead when they started being used to create video as well. They’re experiencing a bit of a decline now, though, as mirrorless cameras start to dominate, and with that comes some unique opportunities. To attach a lens meant for a DSLR to a mirrorless camera, an adapter housing must be used, and [Ancient] found a way to squeeze a computer and a programmable aperture into this tiny space.

The programmable aperture is based on an LCD screen from an old cell phone. LCD screens are generally transparent until their pixels are switched, and in most uses as displays a backer is put in place so someone can make out what is on the screen. [Ancient] is removing this backer, though, allowing the LCD to be completely transparent when switched off. The screen is placed inside this lens adapter housing in the middle of a PCB where a small computer is also placed. The computer controls the LCD via a set of buttons on the outside of the housing, allowing the photographer to use this screen as a programmable aperture.

The LCD-as-aperture has a number of interesting uses that would be impossible with a standard iris aperture. Not only can it function as a standard iris aperture, but it can do things like cycle through different areas of the image in sequence, open up arbitrary parts or close off others, and a number of other unique options. It’s worth checking out the video below, as [Ancient] demonstrates many of these effects towards the end. We’ve seen some of these effects before, although those were in lenses that were mechanically controlled instead.

Continue reading “A Computer That Fits Inside A Camera Lens”

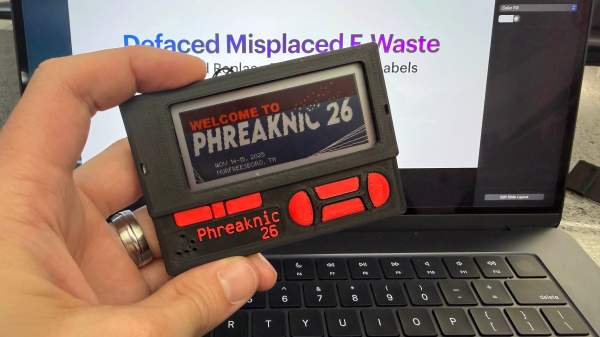

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.