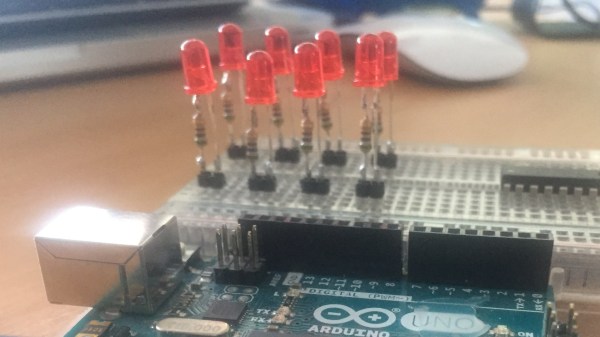

The archetypal “blink an LED” is a great starter project on any platform, but once the bug takes hold that quickly turns into an exploration of exactly how many LEDs a given microcontroller can drive. And that often leads to Charlieplexing. A quick search yields many copies of The Table describing how many LEDs can be driven by a given number of pins but that’s just the most rudimentary way to describe it. Way back in 2013 [M Rule] developed a clever trick to describe the number of LED matrices which can be driven by a Charlieplexed array of a given size that makes this process much more intuitive. The post may be old, but we promise the method is still fresh.

[M Rule] was specifically looking to drive those big, cheap single color LED matrices which are often used to make scrolling signs and the like. These parts are typically a matrix of LEDs with a row of common cathodes and one of common anodes. Internally they are completely dumb and can be driven by row/column scanning, or any other way a typical matrix can be controlled. The question is, given known matrix sizes, how many can be driven with a a number of Charlieplexed LED drive pins?

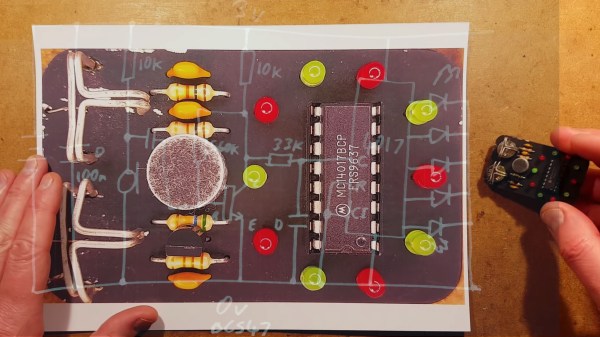

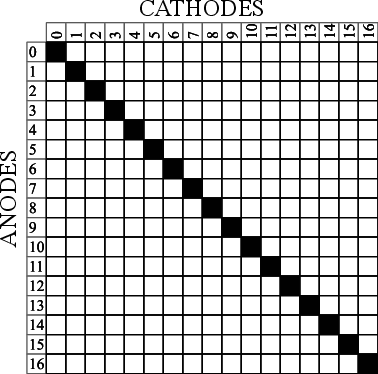

The first step is to visualize the 1D array of available pins as a 2D matrix, as seen to the right. Note each numbered pin is the same on the X and Y, thus the black exclusion zone of illegal drive pin combinations slicing across the graph (you can’t drive an LED connected to one pin twice). The trick, if one were to say it resides in a single place, would be titling the axis anode and cathode, representing two “orientations” the drive pins can be put in. With this diagram [M Rule] observed you can simply drop a matrix into the array. If it fits outside the exclusion zone, it can be driven by those pins!

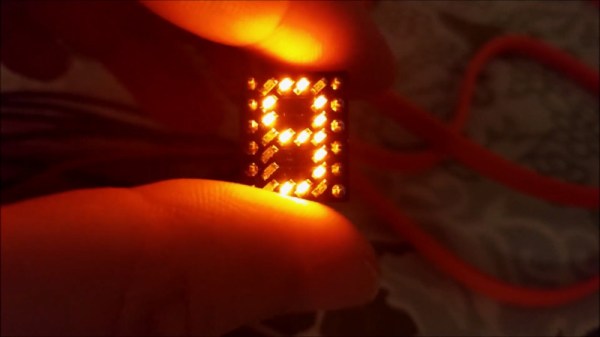

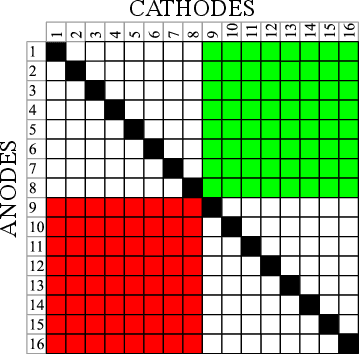

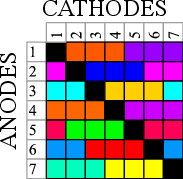

To the left is what this looks like with two 8×8 matrices, one connected between pins 1-8 and 9-16, the other connected between 9-16 and 1-8. This isn’t terribly interesting, but the technique works just as well with single LEDs and any size matrix, including 7-segment displays. Plus as long as an element doesn’t overlap itself it can wrap around the edges leading to some wild visuals, like 14 RGB LEDs on seven pins to the right.

The most extreme examples are pretty exotic. Check out [M Rule]’s post for the crown jewel; 18 pins to drive six 5×7 modules, six 7-segment displays, 12 single LEDs, and 18 buttons!

If this color coded diagram seems familiar, you may be remembering [openmusiclabs]’ excellent diagram describing ways to scan many of buttons. Or our coverage of another trick of matrix topology by [M Rule] from a few weeks ago.