When it’s not just sticking fake gears on things and calling it a day, the Steampunk look is pretty cool. Imagining technology in a world stuck with Victorian aesthetics is a neat idea, and one that translates to the look of other time periods — Fallout, anyone?

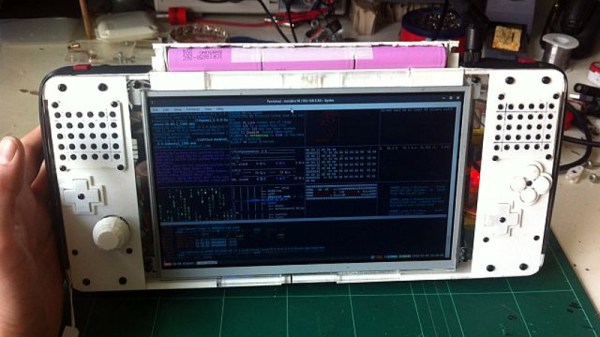

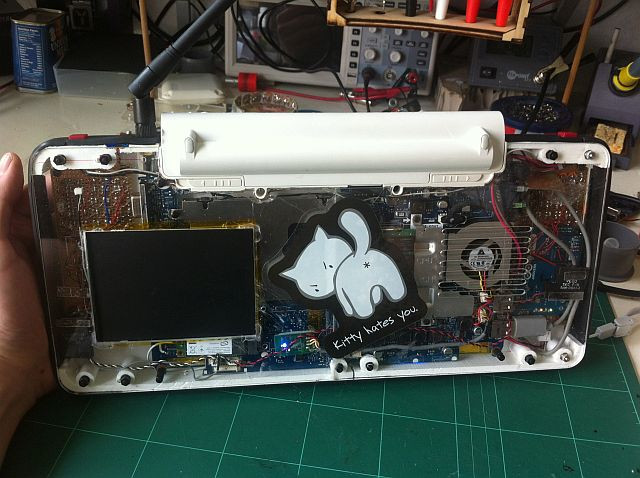

But what if you try to create a technological aesthetic based on a more recent and less celebrated time? That’s what [ghettobastler] has attempted with this somewhat bizarre Minitel-YouTube-VCR mash-up. Taking inspiration from a webcomic’s take on “Formicapunk,” modern tech based on the aesthetic of the wildly successful French videotex service of the 70s and 80s, the system uses a very cool Minitel 1B terminal and a Raspberry Pi 3.

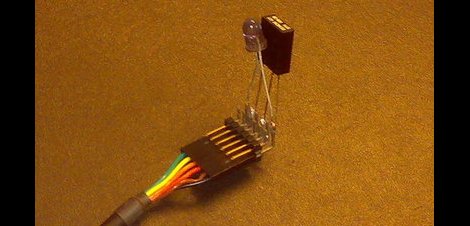

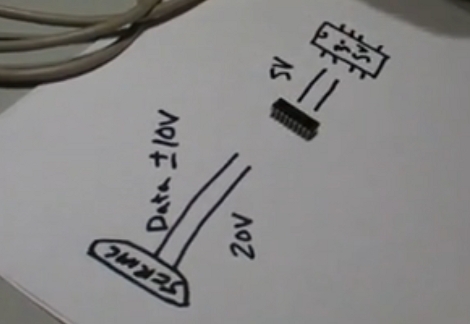

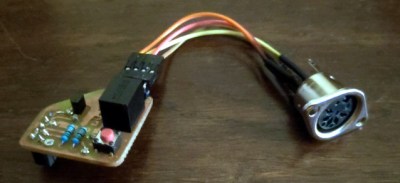

With the help of a level-shifting circuit, the Mintel and the Pi talk over serial, allowing the terminal to be used as, well, a terminal for the Pi. Videos are downloaded from YouTube by the Pi, which sends the video to the VCR from its composite output, and controls the VCR with an IR LED that emulates the original remote. Come to think of it, just watch the video below — it’s probably easier than trying to describe it.

It’s weird, true, but we love the look of that Minitel terminal. Something about it just screams cyberdeck; if anyone has a spare one of these, get busy and put something together for our Cyberdeck Design Contest.

Continue reading “YouTube Like It’s 1970s France With This Minitel-VCR Mashup”