With the powerful off-the-shelf hardware available to us common hardware hobbyist folk, how hard can it be to make a smartphone from scratch? Hence [V Electronics]’s Spirit smartphone project, with the video from a few months ago introducing the project.

As noted on the hardware overview page, everything about the project uses off the shelf parts and modules, except for the Raspberry Pi Compute Module 5 (CM5) carrier board. The LCD is a 5.5″, 1280×720 capacitive one currently, but this can be replaced with a compatible one later on, same as the camera and the CM5 board, with the latter swappable with any other CM5 or drop-in compatible solution.

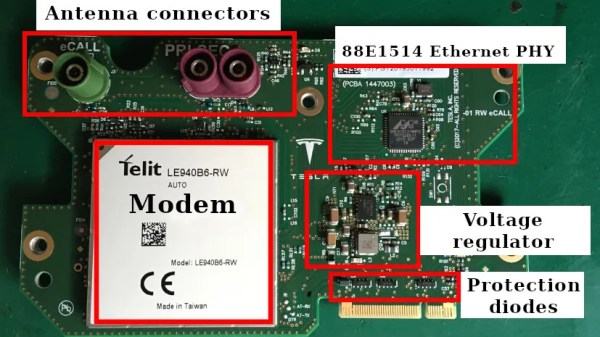

The star of the show and the thing that puts the ‘phone’ in ‘smartphone’ is the Quectel EG25-GL LTE (4G) and GPS module which is also used in the still-not-very-open PinePhone. Although the design of the carrier board and the 3D printable enclosure are still somewhat in flux, the recent meeting notes show constant progress, raising the possibility that with perhaps some community effort this truly open hardware smartphone will become a reality.

Continue reading “Pi Compute Module Powers Fully Open Smartphone”