For several years, [Jim] has wanted to construct a fully-mechanical universal Turing machine. Without the help of any electronic circuits or electrical input, his goal was to build the machine using simple hand tools and scrap materials.

If you are not familiar with the concept of a Turing machine, they are devices that manipulate symbols or input from a strip of tape, according to a set table of rules. By definition, a Turing machine should be adaptable to simulate the logic of any computer algorithm, albeit in a much slower fashion than you would see from a computer.

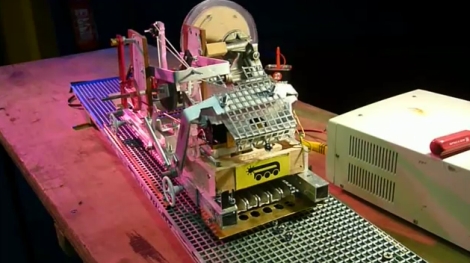

He has replaced the strip of tape with a wire grid, and the symbols have been implemented in the form of ball bearings placed on the aforementioned grid. His hand-cranked machine uses magnets to lift the input symbols from the grid, processing them according to the rules table he routed out of a wood block.

The implementation is definitely clever, though [Jim] admits it is not without its problems. He took it to Maker Faire UK, and most people didn’t quite understand what they were seeing without a full explanation. The machine is not quite as reliable as he would like it to be, and he would like to make it a bit more powerful as it currently would take months to add two numbers together.

Keep reading to see a brief video demo of his Turing machine in action, and check out his blog if you want to see more information on how the machine was built.

Interested in seeing more Turing machines? Check out these two machines we featured a while back.

Continue reading “Mechanical Turing Machine Can Compute Anything…slowly”