When it comes to building particle accelerators the credo has always been “bigger, badder, better”. While the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) with its 27 km circumference and €7.5 billion budget is still the largest and most expensive scientific instrument ever built, it’s physics program is slowly coming to an end. In 2027, it will receive the last major upgrade, dubbed the High-Luminosity LHC, which is expected to complete operations in 2038. This may seem like a long time ahead but the scientific community is already thinking about what comes next.

Recently, CERN released an update of the future European strategy for particle physics which includes the feasibility study for a 100 km large Future Circular Collider (FCC). Let’s take a short break and look back into the history of “atom smashers” and the scientific progress they brought along. Continue reading “Smashing The Atom: A Brief History Of Particle Accelerators”

particle accelerator15 Articles

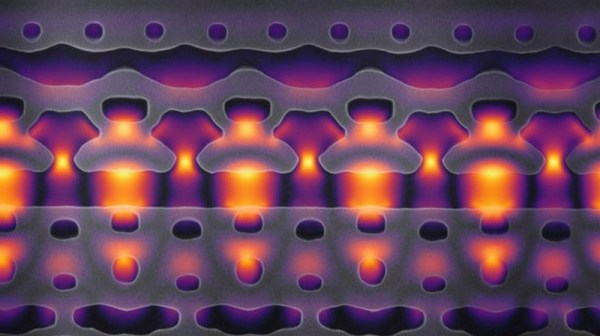

Particle Accelerators That Fit On A Chip

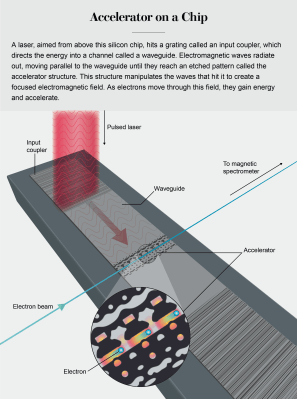

If you were asked to imagine a particle accelerator, you would probably picture a high-energy electron beam contained within a kilometers-long facility, manned by hundreds of engineers and researchers. You probably wouldn’t think of a chip smaller than a fingernail, yet that’s exactly what the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory’s Accelerator on a Chip International Program (ACHIP) has accomplished.

The Stanford University team developed a device that uses lasers to accelerate electrons along etched channels on a silicon chip. The idea for a miniature accelerator has existed since the laser’s invention in 1960, but the requirement for a device to generate electrons made the early proof-of-concepts difficult to manufacture in bulk.

The electromagnetic waves produced by lasers have much shorter wavelengths than the microwaves used in full-scale accelerators, allowing them to accelerate electrons in a far more confined space – channels can be shrunk to three one-thousandths of a millimeter wide. In order to couple the lasers and electrons properly, the light waves must push the particles in the correct direction with as much energy as possible. This also requires the device to generate electrons and transmit them via the proper channel. With an accelerator engraved in silicon, multiple components can fit on the same chip.

Within the latest prototype, a laser hits a grating from above the chip, directing the energy into a waveguide. The electromagnetic waves radiate out, moving with the waveguide until they reach an etched pattern that creates a focused electromagnetic field. As electrons move through the field, they accelerate and gain energy.

The results showed that the prototype could boost the electrons by 915 electron volts, equivalent to the electrons gaining 30 million electron volts over a meter. While the change is not on the scale of SLAC, it does scale up more easily since researchers can fit multiple accelerating paths onto future designs without the bulk of a full-scale accelerator. The chip exists as a single stage of the accelerator, allowing more researchers to conduct experiments without the need to reserve space in expensive full-scale particle accelerators.

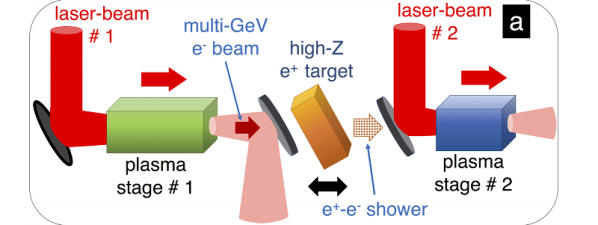

Creating Antimatter On The Desktop — One Day

If you watch Star Trek, you will know one way to get rid of pesky aliens is to vent antimatter. The truth is, antimatter is a little less exotic than it appears on TV, but for a variety of reasons there hasn’t been nearly as much practical research done with it. There are well over 200 electron accelerators in labs around the world, but only a handful that work with positrons, the electron’s anti-counterpart. [Dr. Aakash Sahai] would like to change that. He’s got a new design that could bring antimatter beams out of the lab and onto the desktop. He hasn’t built a prototype, but he did publish some proof-of-concept simulation work in Physical Review Accelerators and Beams.

Today, generating high-energy positron beams requires an RF accelerator — miles of track with powerful electromagnets, klystrons, and microwave cavities. Not something you are going to build in your garage this year. [Sahai] is borrowing ideas from electron laser-plasma accelerators (ELPA) — a technology that has allowed electron accelerators to shrink to mere inches — and turned it around to create positrons instead.

Continue reading “Creating Antimatter On The Desktop — One Day”

Military Surplus Repurposed For High Energy Physics

Performing high-energy physics experiments can get very expensive, a fact that attracts debate on public funding for scientific research. But the reality is that scientists often work very hard to stretch their funding as far as they can. This is why we need informative and entertaining stories like Gizmodo’s How Physicists Recycled WWII Ships and Artillery to Unlock the Mysteries of the Universe.

The military have specific demands on components for their equipment. Hackers are well aware MIL-SPEC parts typically command higher prices. That quality is useful beyond their military service, which lead to how CERN obtained large quantities of a specific type of brass from obsolete Russian naval ordnance.

The remainder of the article shared many anecdotes around Fermilab’s use of armor plate from decommissioned US Navy warships. They obtained a mind-boggling amount – thousands of tons – just for the cost of transport. Dropping the cost of high quality steel to “only” $53 per ton (1975 dollars, ~$250 today) and far more economical than buying new. Not all of the steel acquired by Fermilab went to science experiments, though. They also put a little bit towards sculptures on the Fermilab campus. (One of the few contexts where 21 tons of steel can be considered “a little bit”.)

Continue reading “Military Surplus Repurposed For High Energy Physics”

There Is No Parity: Chien-Shiung Wu

Hold out your hands in front of you, palms forward. They look quite similar, but I’m sure you’re all too aware that they’re actually mirror images of each other. Your hands are chiral objects, which means they’re asymmetric but not superimposable. This property is quite interesting when studying the physical properties of matter. A chiral molecule can have completely different properties from its mirrored counterpart. In physics, producing the mirror image of something is known as parity. And in 1927, a hypothetical law known as the conservation of parity was formulated. It stated that no matter the experiment or physical interaction between objects – parity must be conserved. In other words, the results of an experiment would remain the same if you tired it again with the experiment arranged in its mirror image. There can be no distinction between left/right or clockwise/counter-clockwise in terms of any physical interaction.

The nuclear physicist, Chien-Shiung Wu, who would eventually prove that quantum mechanics discriminates between left- and right-handedness, was a woman, and the two men who worked out the theory behind the “Wu Experiment” received a Nobel prize for their joint work. If we think it’s strange that quantum mechanics works differently for mirror-image particles, how strange is it that a physicist wouldn’t get recognized just because of (her) gender? We’re mostly here to talk about the physics, but we’ll get back to Chien-Shiung Wu soon.

The End of Parity

Conservation of parity was the product of a physicist by the name of Eugene P. Wigner, and it would play an important role in the growing maturity of quantum mechanics. It was common knowledge that macro-world objects like planets and baseballs followed Wigner’s conservation of parity. To suggest that this law extended into the quantum world was intuitive, but not more than intuition. And at that time, it was already well known that quantum objects did not play by the same rules as classical objects. Would quantum mechanics be so strange as to care about handedness? Continue reading “There Is No Parity: Chien-Shiung Wu”

How Does A Voltage Multiplier Work?

If you need a high voltage, a voltage multiplier is one of the easiest ways to obtain it. A voltage multiplier is a specialized type of rectifier circuit that converts an AC voltage to a higher DC voltage. Invented by Heinrich Greinacher in 1919, they were used in the design of a particle accelerator that performed the first artificial nuclear disintegration, so you know they mean business.

Theoretically the output of the multiplier is an integer times the AC peak input voltage, and while they can work with any input voltage, the principal use for voltage multipliers is when very high voltages, in the order of tens of thousands or even millions of volts, are needed. They have the advantage of being relatively easy to build, and are cheaper than an equivalent high voltage transformer of the same output rating. If you need sparks for your mad science, perhaps a voltage multiplier can provide them for you.

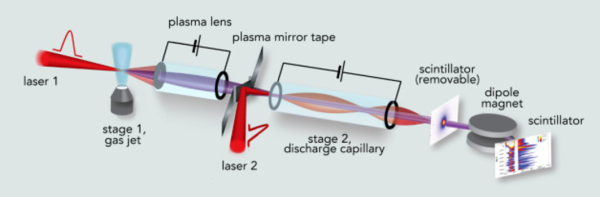

VHS-Tape-Plasma Mirror Drives Tiny Particle Accelerator

When you think of a particle accelerator, you’re probably thinking of tens of kilometers of tube buried underground, at high vacuum, that uses precisely timed electromagnetic fields to push charged particles like electrons up to amazing speeds (and energies). However, it’s also possible to accelerate electrons in other ways, and lasers are a good bet. Although a laser-based particle accelerator can push electrons very effectively for a few centimeters, they top out at a relatively low maximum “speed” of a couple billion electron-volts, as opposed to the trillions of eV that you can get out of a really big traditional accelerator.

If only you could repeat the laser trick again, “hitting” the already-moving electrons from behind with another beam, you could boost them up to even higher energies. Doing so would take something like a one-way mirror that lets the electrons pass through, but that you could then bounce a laser beam off of. In a fantastic mixture of science and mother-of-invention-style hacking, these scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Labs use plain-old VHS tape to make plasma mirrors to do just that. Why VHS tape? Because it’s cheap, flexible, and easy to move through the apparatus at high speeds.

The device works like this: a first laser beam passes through a jet of ionized gas and pulls some electrons with it. These electrons are then focused into a beam and pass through some (moving) VHS tape. The electrons punch a hole through the tape. In their wake they leave a hot plasma of mid-90s TV shows you never got around to watching. The second laser beam is then bounced off this plasma mirror and further accelerates the electron beam from behind. In principle, you could repeat this second stage enough times to build up the energy you needed, but for now the crew is working to characterize their single-stage beam. Getting the timing right on the second-stage beam is, naturally, non-trivial.

Anyone who has spent some time in a science lab knows that there are millions of these tiny get-it-done-quick hacks behind the scenes, but it’s nice to see one take center stage as well. If you’ve got stories of great lab hacks that you’d like to see us cover, post up in the comments!

Thanks [Bruce] for the tip, via Science Daily.